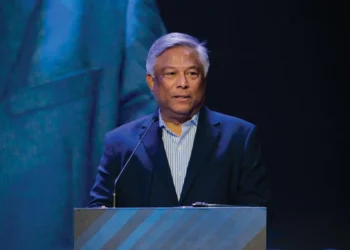

Former NSW regulator Paul Newson questions whether Australia’s long-held approach to casino regulation is still relevant today.

Australia’s casino probity regime is a relic of regulatory logic forged in a different era. Rooted in the foundational Street and Connor reports, it was designed to shield the industry from infiltration by organized crime, borrowing heavily from the Las Vegas playbook. These reports recommended adopting a dedicated licensing regime modelled on the US approach, centered on rigorous scrutiny of individuals – financial history, associations, character – as the cornerstone of casino integrity.

But what was once a rational safeguard has become an outdated orthodoxy. Today, the greatest threats to integrity in the sector stem not from criminal figures seeking access to casinos, but from within: governance failures, ethical drift and leadership strategies that prioritize profit over principle.

But what was once a rational safeguard has become an outdated orthodoxy. Today, the greatest threats to integrity in the sector stem not from criminal figures seeking access to casinos, but from within: governance failures, ethical drift and leadership strategies that prioritize profit over principle.

The casino sector has changed

The major casino scandals that rocked Australia are now well traversed. The real story today is transformation, particularly at Crown, which has repositioned itself as a champion of ethical leadership. Its internal mantra, asking “should we” rather than “can we”, has come to symbolize the cultural shift needed to restore integrity and rebuild trust.

Crown’s journey reveals the real levers of reform: leadership accountability, risk culture and ethical governance. But it also exposes the ongoing misalignment of a probity system that continues to prioritize individual background checks over institutional conduct.

A framework that has lost its purpose

The current probity system is highly invasive, operationally burdensome and increasingly difficult to justify. Applicants, especially those operating across multiple jurisdictions, must endure redundant and exhaustive assessments of their personal affairs, often with limited regard to practical risk or contemporary organizational context. Mutual recognition is rare and regulators expend substantial resources verifying information that rarely relates to the real drivers of misconduct.

Decades after the Connor and Street Reports rightly recommended strict regulatory controls to prevent criminal infiltration, the regulatory model remains anchored in the image of Bugsy Siegel – not today’s environment where misconduct is born from boardrooms, not back rooms. The greatest threats are now internal: a culture of legal minimalism, board apathy and unethical leadership.

Time and again, major regulatory failures have emerged not from inadequately vetted individuals but from toxic cultures, conflicted remuneration structures, poor board oversight and regulatory inattention. These risks cannot be screened out via a probity checklist: they must be governed and led.

Time and again, major regulatory failures have emerged not from inadequately vetted individuals but from toxic cultures, conflicted remuneration structures, poor board oversight and regulatory inattention. These risks cannot be screened out via a probity checklist: they must be governed and led.

Outdated effort, diminishing returns

What’s more concerning is that reliance on front-loaded, high-threshold probity checks for individuals has become a dismal form of risk mitigation in a mature, largely corporate market. It is an over-engineered gateway that ignores the need for intelligent, ongoing supervision and agile regulatory tools.

Australia has made virtually no policy investment in modernizing this legacy framework. It persists by inertia, not because it’s delivering measurable outcomes. The regulatory effort often lacks innovation. Some regulators still herald the number of audits or investigations completed as if volume alone equates to impact. It’s a model of regulatory theatre: activity masquerading as effectiveness.

Australia has made virtually no policy investment in modernizing this legacy framework. It persists by inertia, not because it’s delivering measurable outcomes. The regulatory effort often lacks innovation. Some regulators still herald the number of audits or investigations completed as if volume alone equates to impact. It’s a model of regulatory theatre: activity masquerading as effectiveness.

What’s needed is not more forms and checks but smarter engagement. Regulators must become intelligence-led, risk-sensitive and outcomes-focused. That means knowing where real vulnerabilities lie, intervening early and applying pressure where it drives cultural change, not where it simply checks a box.

The evidence is in

The Victorian Royal Commission into Crown Melbourne laid bare a catalogue of misconduct: dishonesty, money laundering, regulatory bullying and exploitation of vulnerable patrons. These behaviors were not committed by individuals with shady pasts. They were enabled by boardrooms that tolerated ethical shortcuts and legal minimalism.

A particularly egregious example came from The Star, which facilitated the use of China UnionPay cards to disguise gambling spend as hotel accommodation. This allowed patrons to sidestep controls on using Chinese-issued cards for gaming purposes, an ethically compromised and potentially unlawful workaround that required institutional coordination, not individual deception. It reflected strategic intent, not failure of probity.

The financial sector has told the same story. The 2018 Prudential Inquiry into the Commonwealth Bank found widespread compliance failures and cultural malaise, not because of poor individual integrity but because of inadequate leadership, risk governance and internal challenge.

If these failures have taught us anything, it’s that ethical collapse is rarely the product of who gets through the door. It’s about what’s tolerated inside once they’re there.

A smarter, risk-based future

A smarter, risk-based future

The current probity regime has failed the test of outcomes. It burdens applicants, slows down productive investment and ties up regulatory effort in low-impact reviews. Reform is overdue and should include:

- Streamlining and harmonization, with mutual recognition across jurisdictions to reduce duplication

- Pivoting from personal to organizational risk, focusing on governance practices, culture and ethical posture

- Rebalancing regulatory resourcing toward early detection, risk profiling and conduct and cultural intelligence

- Recognizing leadership maturity, particularly where organizations have undertaken substantial reform and demonstrated ethical turnaround

Integrity still matters, but how we assess and ensure it must evolve.

Conclusion

Probity checks based on legacy fears no longer serve today’s risk landscape. They offer diminishing returns, distort regulatory focus and act as a drag on innovation and uplift in the sector.

Worse, they reflect a broader regulatory malaise – where volume-led inspection programs are celebrated as accomplishments, regardless of their actual impact. Declaring 500 audits completed may sound impressive, but if those audits revolve around checking machine stickers or administrative compliance, we are simply measuring activity, not outcomes.

This superficial engagement crowds out more meaningful regulatory work: the development of sophisticated intelligence functions, effective monitoring of high-risk conduct and the clear communication of regulatory expectations. Historically, casino and gaming surveillance functions have failed to provide persuasive deterrence or real-time insight into emerging risks. To deliver genuine sector uplift, regulators must shift from box-ticking to risk signaling – proactively identifying vulnerabilities, guiding reform and targeting oversight where it matters most.

This superficial engagement crowds out more meaningful regulatory work: the development of sophisticated intelligence functions, effective monitoring of high-risk conduct and the clear communication of regulatory expectations. Historically, casino and gaming surveillance functions have failed to provide persuasive deterrence or real-time insight into emerging risks. To deliver genuine sector uplift, regulators must shift from box-ticking to risk signaling – proactively identifying vulnerabilities, guiding reform and targeting oversight where it matters most.

The future of industry supervision lies not in scouring personal bank statements but in examining board and senior management conduct, organizational culture and incentive structures. This must be underpinned by effective monitoring of actual behavior and a regulatory effort anchored in a clear-eyed understanding of where the greatest risks truly lie.