It’s official: Macau is no longer the center of the casino gaming universe. The Macau dream is over – for the foreseeable future at least – after a stupendous 18-year run the likes of which the casino gambling world has never seen before and may never see again. IAG Vice Chairman and CEO Andrew W Scott gives his take on why it has all gone so wrong for Macau, and whether the SAR can ever recapture its crown.

“The king is dead. Long live the king.”

“The king is dead. Long live the king.”

First declared in 1422 upon the death of the French King Charles VI and the instantaneous accession to the throne of his son, King Charles VII, this evocative proclamation full of history and tradition is uttered only on the exceedingly rare and momentous occasion of the passing of the crown from one monarch to the next.

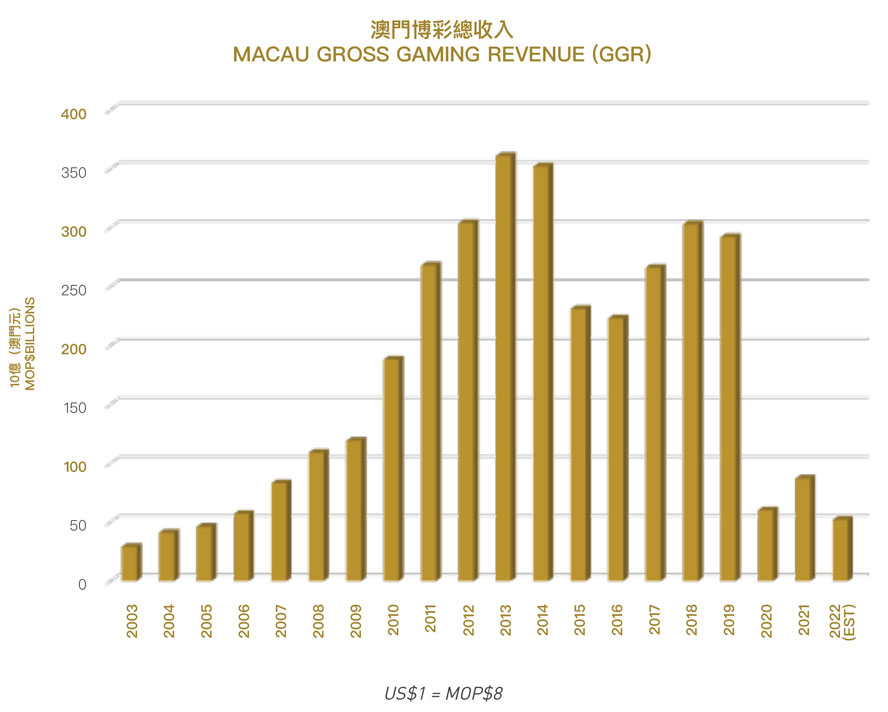

And so too, it’s time to make this declaration for the global gaming industry. The harsh reality is that Macau – the undisputed king since surpassing Las Vegas in gross gaming revenue (GGR) in 2007 – is king no more. For the 30 months since the pandemic hit, GGR has ranged, on a calendar monthly basis, from as low as 3% to as high as 43% of 2019 levels, with an average of just 24% throughout the entire pandemic.

Meanwhile, in a booming post-COVID recovery many thought impossible, the state of Nevada has booked over US$1 billion in GGR every month since March 2021 – with the lion’s share from Las Vegas, of course. This is approximately 50% higher than the Macau average throughout the entire pandemic and around triple the GGR run rate of Macau’s last completed quarter, 2022 Q2. Even traditionally much smaller jurisdictions like the Philippines, Singapore and Australia are beating or in the ballpark of Macau’s last quarter.

2004 TO 2013

2004 TO 2013

Macau’s arguably most historic gaming company, STDM, founded by the legendary Dr Stanley Ho, held the city’s monopoly casino gaming concession from 1960 to 2000. In the wake of the handover of Macau from Portugal to China on 20 December 1999, the concession was extended to 2002, after which the industry was liberalized with the addition of Wynn Macau and Galaxy Entertainment, creating a triumvirate of industry operators. Subsequent sub-concessions were granted to Venetian Macao (now Sands China), MGM China and Melco-PBL (now Melco Resorts), expanding the triumvirate into a sextet. It took until 18 May 2004 for Sands to open their first property – Sands Macao – on the Macau peninsula near the Hong Kong-Macau ferry terminal. Two months later Galaxy’s first casino opened across the road at the Waldo hotel and the shiny new industry was off to the races.

What we were to witness over the next decade was nothing short of miraculous. Each of the six concessionaires opened a world-class five-star property – Grand Lisboa, MGM Macau, Sands Macao, StarWorld and Wynn Macau on the Macau peninsula and Crown Macau (now Altira) in Taipa. Three followed up with even greater offerings in Cotai – City of Dreams, Galaxy Macau and The Venetian Macao. Gross gaming revenue (GGR) grew from MOP$29 billion (US$3.6 billion) in 2003, the last year of monopoly operations, to MOP$361 billion (US$45.1 billion) in 2013, the still-reigning high-water mark of Macau GGR. That represents a decade-long compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of a mind-boggling 28.7% – and don’t forget that decade included the global financial crisis of 2007 and 2008.

2014 TO 2019

2014 TO 2019

The next six years heralded the first headwinds and were more nuanced than the rampant growth of the preceding decade.

The year 2014 saw the first reduction in GGR for Macau’s liberalized industry. Admittedly it was only a 2.5% fall, but still represented a shock after a decade-long unbroken streak of annual growth, with year-on-year growth rates ranging from “only” 9% (in 2009 post-GFC) to 58% (in 2010, making up for the 2009 “stall”).

Initially, and laughably, the 2014 hiccup was blamed on the FIFA World Cup in Brazil that year, the postulation being that gamblers had stayed home to bet on the quadrennial global football festival. That theory was thoroughly discredited in 2015 when the so-called “crackdown on corruption” hit Macau, causing a 34% year-on-year collapse of GGR. The crackdown had begun a couple of years earlier but took a while to gain momentum and bite Macau. The VIP sector was hit particularly hard.

But by 2018 the industry had weathered the storm, to see GGR claw back to MOP$303 billion (US$37.9 billion), some 84% of the 2013 peak. While the 2019 GGR of MOP$292 billion (US$36.5 billion) represented a 3.6% year-on-year decline, the mood on the ground was that the industry had perhaps stabilized, leaving its rapid growth phase behind it to now enter a new phase of maturity characterized by single digit annual growth rates.

No one on God’s green earth could possibly have predicted the calamity that was in store just around the corner.

2020 TO TODAY: THE COVID CRISIS

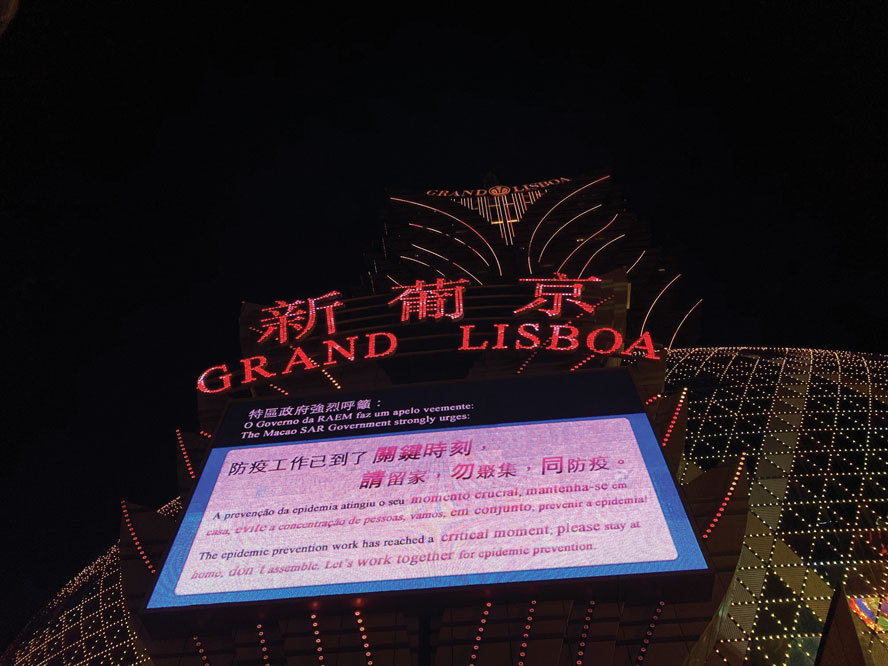

So many column-inches in newspapers, magazines and websites have been devoted to COVID it is unnecessary to elaborate here beyond the thinnest of details. Smashing into Macau in the late January Chinese New Year of 2020 like the meteor that wiped out the dinosaurs, COVID-19 saw the surreal and utterly unprecedented closure of all Macau casinos from 5 to 20 February 2020. It was the first time in living memory they had closed en masse. But worse than this 15-day economic-zero was the endless series of rolling border closures and travel restrictions, along with their near-absolute chilling effect on visitation from mainland China.

From the 2019 GGR of MOP$292 billion (US$36.5 billion), Macau crashed by 80% year-on-year to a dismal MOP$60 billion (US$7.5 billion) in 2020. We saw a meagre improvement in 2021 to MOP$87 billion (US$10.9 billion), still only 30% of 2019 levels. But the first half of 2022 has been even worse than the preceding two years, with GGR a paltry MOP$26 billion (US$3.3 billion), a run rate just 18% of 2019 levels. It was the worst half-year of the 2.5 years of pandemic-affected business so far, from January 2020 to June 2022.

And just when we thought it couldn’t get any worse, it did. The most recent quarter, 2022 Q2, ran at a miserable 12% of 2019 and July (not yet completed at the time of writing) could be the worst month since the pandemic began, with severe border restrictions in the first 10 days of the month followed by total casino closures from 11 July onwards. My guess is that July could come in around 2% of the 2019 monthly average – effectively economic-zero.

And just when we thought it couldn’t get any worse, it did. The most recent quarter, 2022 Q2, ran at a miserable 12% of 2019 and July (not yet completed at the time of writing) could be the worst month since the pandemic began, with severe border restrictions in the first 10 days of the month followed by total casino closures from 11 July onwards. My guess is that July could come in around 2% of the 2019 monthly average – effectively economic-zero.

THERE IS NO NORMAL COMING

THERE IS NO NORMAL COMING

We’ve been hearing the same question repeatedly for 2.5 years, “When will things return to normal?” And the answer from so-called “experts,” yours truly included, has always been the same – some variation on “next year,” “three quarters from now” or “surely this can’t continue.”

But these are just platitudes, not based on anything other than assumption, presumption or compunction. The cold, hard truth is there is no end in sight to the economic-zero Macau is suffering. I have given up predicting when Macau will be “normal” again, whatever that means, and anyone who says they know is lying. No one knows. The Chief Executive of Macau predicted in November last year that the 2022 GGR would be MOP$130 billion. He will be way off the mark, with revenue likely to be less than half that amount.

It could easily be a third of that amount, or even less! It’s time to stop crying wolf. I think it’s likely we will effectively never see “normal” again – especially if your definition of “normal” is 2019 levels.

In mid-July the trio of US operators with exposure to Macau sat shoulder to shoulder for an interview on CNBC. Las Vegas Sands Chairman and CEO Rob Goldstein, MGM Resorts CEO Bill Hornbuckle and Wynn Resorts CEO Craig Billings dutifully proclaimed Macau would return to its former glory days.

“I find it funny that people question Macau’s return,” Goldstein said, “Of course it’s been a hard couple of years, no question … it’s a tough time. You’ve got to basically hunker down and wait for it to turn. But the idea it doesn’t turn is kind of hard to imagine – it’s going to turn probably this year or next. And when it does, Macau will go back to making – you know, we made at the peak US$3.5 billion EBITDA. I think we’ll make a lot more than that in the future there.”

“I find it funny that people question Macau’s return,” Goldstein said, “Of course it’s been a hard couple of years, no question … it’s a tough time. You’ve got to basically hunker down and wait for it to turn. But the idea it doesn’t turn is kind of hard to imagine – it’s going to turn probably this year or next. And when it does, Macau will go back to making – you know, we made at the peak US$3.5 billion EBITDA. I think we’ll make a lot more than that in the future there.”

Hornbuckle added, “Macau was seven, eight times [the GGR of] Las Vegas … so it comes back half to begin with and then some and then some. It’s the largest gaming market in the world bar none, and it will forever be.”

If the Chief Executive of Macau can’t predict what will happen in Macau, and doesn’t know whether the city will be locked down or not in a week’s time, how on earth can Mssrs Goldstein, Hornbuckle and Billings know what’s going to happen? With all due respect – and I have plenty of that for the trio – they’re stuck between a rock and a hard place. Between them they have tens of billions of dollars invested in irremovable bricks and mortar on terra firma in Macau. The concessionaires as a cohort have run up their debt from around US$5 billion to over US$20 billion during the COVID catastrophe. And the retendering process is looming in the coming few months. Under such circumstances they have no choice but to publicly affirm their commitment to Macau and act as cheerleaders assuring one and all that “the good times will roll again.” To do anything else sends a signal to the Macau government and the global investment community that could prove disastrous for their companies.

MACAU KILLER NUMBER 1: COVID-ZERO

It’s long been proven that the concomitant consequence of Macau’s COVID-zero policy is a state of economic-zero for the city.

While the rest of the world learns to live with the virus, mainland China has adopted a strict COVID-zero approach. And where mainland China leads, Macau follows. A good chunk of that is due to the political obsequiousness of the Macau government to its mainland overlords, but there is a practical reason too – Macau traditionally relies on the mainland for some 60% of its visitation and some 90% of its GGR, so there is a commercial pressure to align its approach with that of its dominant feeder market.

At under 700,000 population, Macau is but a pimple compared to the 1.4 billion-strong mainland China, and on top of that the mainland correctly perceives Macau as rolling in cash because of the extended boom of the 2000s and 2010s, so the PRC isn’t going to take Macau into account one iota in its decision-making process when it comes to relaxing the COVID-zero policy.

At under 700,000 population, Macau is but a pimple compared to the 1.4 billion-strong mainland China, and on top of that the mainland correctly perceives Macau as rolling in cash because of the extended boom of the 2000s and 2010s, so the PRC isn’t going to take Macau into account one iota in its decision-making process when it comes to relaxing the COVID-zero policy.

While markets like the Philippines, Singapore, Australia and the rest of the Asia-Pacific region are all opening their borders, putting COVID behind them and even starting to see a boom in “revenge travel,” there is no end in sight to China’s COVID-zero policy. China and its two SARs of Hong Kong and Macau are starting to look like global outliers – increasingly and perplexingly so – in the eyes of the rest of the world.

MACAU KILLER NUMBER 2: CHINA’S POSTURE TOWARD MACAU

Despite all the doom and gloom, if it were only COVID that was killing Macau, it would not be right to dethrone the SAR as the king of the casino gaming universe, as it would be reasonable to assume Macau would bounce back post-COVID, just as Las Vegas and many other jurisdictions have done. But there is a second group of factors – currently somewhat masked by the presence of COVID – that will continue to strangle Macau long after COVID is done and dusted.

These other factors stem from the fact that mainland China has great antipathy towards the city’s core activity of casino gambling. Casino gambling is illegal throughout the mainland and disparaged there as a scourge on society. It is begrudgingly tolerated in Macau by the PRC only because of its historical context – dating back to the mid-19th century as a legal activity and for centuries more as a major de facto cultural characteristic of Macau.

These other factors stem from the fact that mainland China has great antipathy towards the city’s core activity of casino gambling. Casino gambling is illegal throughout the mainland and disparaged there as a scourge on society. It is begrudgingly tolerated in Macau by the PRC only because of its historical context – dating back to the mid-19th century as a legal activity and for centuries more as a major de facto cultural characteristic of Macau.

As well as being fuelled by ideology (and remember, ideology always trumps commercial considerations in mainland China), this antipathy is further driven by a number of past and present Macau peculiarities surely despised by the PRC. It is well known the Macau casino industry was used by wealthy Chinese, particularly in the 2010s and primarily through junkets, as a major vehicle for capital flight from China. Expatriation of billions of dollars in profits to the US via the American operators would also have been a bitter pill to swallow, and a pill which no doubt has become increasingly bitter as the animosity between the two world superpowers has grown in the past five to 10 years. These profits were generated on the back of the casino play of the people of mainland China – so the PRC perceives this as a form of wealth transfer from its shores to that of its geopolitical foe. China often cites “gambling-related crime” as a social evil, and no doubt resents the increase in problem gambling issues within the mainland’s borders, exported from Macau.

There is a wide range of ways in which this antipathy to Macau’s casino gaming industry is being expressed – and in an increasingly overt fashion – by the mainland and, as a proxy, by the Macau government itself. The utter destruction of Macau’s VIP industry in late 2021 is one. The refusal to allow electronic processing of visas for mainland visitors to Macau is another. Yet another is the clamping down on travelling to gamble by China’s National Immigration Administration which has publicly stated its goal to “keep gambling-related persons within [mainland China] to the maximum extent possible.” In recent times mainland gamblers visiting Macau have been probingly questioned – some might say harassed – by mainland officials regarding the reasons for their trips to Macau and their source of funds.

The mainland relentlessly demands Macau diversify its economy away from gambling. But this is almost futile – a mission impossible for Macau given its history, its land resources (putting aside for another day the whole question of Hengqin Island, which has its own set of issues), its population and their skill set as well as the SAR’s total lack of economic comparative advantage in anything other than the provision of casino gambling in the region. The sole arguable exception to this is the idea of Macau acting as a gateway for Lusophone trade with China – although there are scale and infrastructure issues making the proposal somewhat problematic. Simply put, Macau is no Hong Kong.

Seemingly oblivious to the fact it is biting the hand that feeds it, the raft of changes in the new gaming law introduced by the Macau government in late 2021 and early 2022, and subsequently passed by the Macau Legislative Assembly in June, were presented as “necessary for the healthy and sustainable development of the industry.” The numerous changes were all negative for the concessionaires, with one debateable minor exception – the changes to satellite casinos. Space precludes a detailed explanation, but avid readers will be familiar with the tens of thousands of words IAG has published on the new law and its negative consequences for the six operators.

Things are likely only to worsen as the years roll on in the second half of the 50 years of the “One Country, Two Systems” regime. For example, some commentators have suggested the mainland may develop a centralized and government-controlled digital RMB, and force gamblers to bet in Macau using such a currency. If this were to happen, which does seem likely sooner or later, the source of funds of every bet in Macau will become a matter of government record. An article published way back in the June 2008 issue of IAG contained a passage which was recently brought to my attention. Written by Andrew MacDonald and the late Bill Eadington, it read:

“No one knows for sure what Beijing may be thinking for the long term, or what levers they may want to pull to rein in the runaway growth and economic dynamic of Macau.”

How prophetic those words have proved to be.

CAN MACAU EVER RECLAIM ITS CROWN?

CAN MACAU EVER RECLAIM ITS CROWN?

Despite this proclamation dethroning Macau as king of the global casino gaming industry, it can take the crown once again. Should COVID finally be put behind us, that will see the end of the first Macau killer. But the second Macau killer – China’s posture towards Macau – will be with us for years to come, barring some unlikely about-face by the PRC. With the destruction of the VIP industry, a heavy crackdown on gamblers from China generally and the much stricter enforcement of China’s US$50,000 annual cap on funds taken by its citizens out of the mainland, Macau’s only option is to pivot to a mass market-focused offering – much along the lines of Las Vegas.

Under such circumstances, the infrastructure of Macau in terms of hotel rooms, public transport and immigration processing is insufficient to support GGR anywhere near the dizzying heights of 2013 or 2019. Sure, Hengqin can help with hotel rooms but that whole Guangdong-Macau experiment is many years away from a mature realization, if that can even be achieved at all. Given this scenario, I would estimate Macau could – in the most favorable of circumstances and with no virus in sight – support a GGR of perhaps US$1 billion per month at best, a total of US$12 billion per year and only a third of 2019 levels. This would put Macau neck and neck with Las Vegas, which is consistently booking a similar level of GGR. Of course EBITDA would not drop by so much, given the much lower margin on the now-lost VIP play, and under this scenario EBITDA could eventually recover to about two-thirds of 2019 levels — noting that this is a generous estimate.

Whether Macau can do this or not remains to be seen in the years ahead, but my counsel is – don’t hold your breath!