The appointment of a special manager with powers to oversee governance of Australia’s Crown Resorts for the next two years presents some unique challenges, writes former regulator David Green.

While the Finkelstein Royal Commission recommended Crown Melbourne be allowed two years in which to re-establish its suitability to hold a casino license, it clearly feared recidivism. To mitigate that concern it opted for the appointment of a “special manager” to serve as the company’s ultimate decision maker. The Victorian government has announced the appointment to that role of Stephen O’Bryan QC, a former Commissioner of the State’s Independent Broad-based Anti-corruption Commission (IBAC).

His instrument of appointment has not been made public, but the broad scope of the special manager’s powers and responsibilities is detailed in a Bill currently before Parliament which will substantially amend Victoria’s casino and gambling legislation when it is enacted. It is that Bill which indicates some of the challenges which the Board of Crown Melbourne is likely to face in exercising its functions while subject to the effective control of Mr O’Bryan.

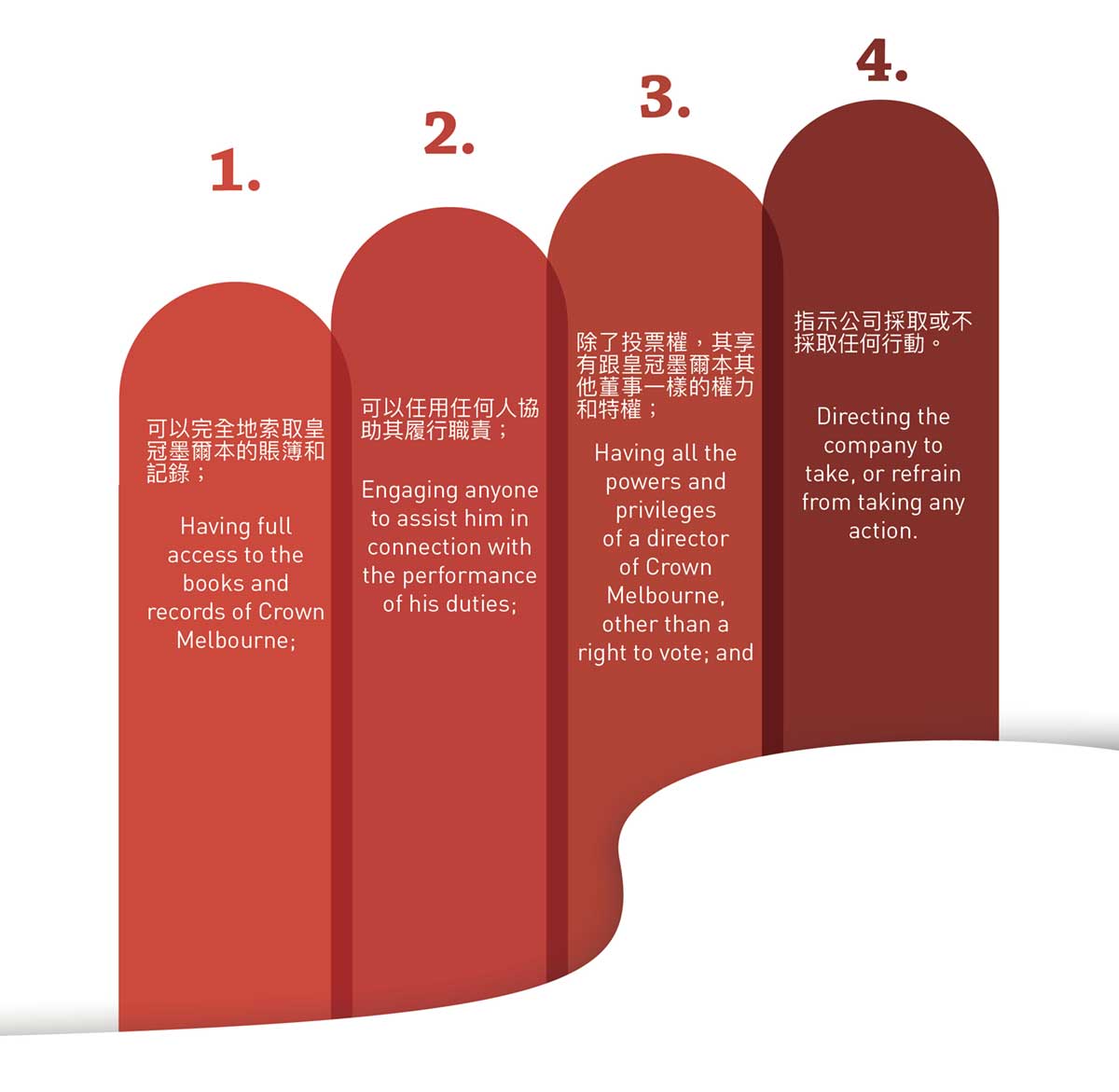

Notably, his powers will include:

There is no requirement contained within the Bill that the appointee to the role of special manager must be “suitable” to occupy the position. The Bill provides that the special manager is not an associate of the casino operator; if he were an associate, he would be required to undergo a suitability assessment, including evaluation of suitability to occupy that role. While a former IBAC Commissioner is undoubtedly “fit and proper”, a test of suitability to occupy such an oversight role arguably would require more, such as relevant industry or regulatory, rather than investigative experience. Similarly, there is no threshold suitability requirement for contractors the special manager may engage to assist him. Presumably their terms of engagement would preclude conflicts of interest, and require confidentiality undertakings, but without a probity evaluation it is impossible to dimension the risk that a contractor with access to confidential or commercially sensitive company records might pose, irrespective of their ostensible affiliation or reputation.

There is no requirement contained within the Bill that the appointee to the role of special manager must be “suitable” to occupy the position. The Bill provides that the special manager is not an associate of the casino operator; if he were an associate, he would be required to undergo a suitability assessment, including evaluation of suitability to occupy that role. While a former IBAC Commissioner is undoubtedly “fit and proper”, a test of suitability to occupy such an oversight role arguably would require more, such as relevant industry or regulatory, rather than investigative experience. Similarly, there is no threshold suitability requirement for contractors the special manager may engage to assist him. Presumably their terms of engagement would preclude conflicts of interest, and require confidentiality undertakings, but without a probity evaluation it is impossible to dimension the risk that a contractor with access to confidential or commercially sensitive company records might pose, irrespective of their ostensible affiliation or reputation.

It is not clear what “powers and privileges” the special manager will enjoy as a director of Crown Melbourne. He will have the right to attend Board and Committee meetings and examine records anyway. He will also be able to participate in a deliberative capacity in those meetings. What is potentially troubling, though, is the fact that he will not have any of the obligations, duties or liabilities of a director of Crown Melbourne. In particular, he will owe no fiduciary duty to the company, to Crown Resorts, as its group holding company, or to the listed company’s shareholders. This asymmetry is possibly unique in a solvent Australian company.

It is not clear what “powers and privileges” the special manager will enjoy as a director of Crown Melbourne. He will have the right to attend Board and Committee meetings and examine records anyway. He will also be able to participate in a deliberative capacity in those meetings. What is potentially troubling, though, is the fact that he will not have any of the obligations, duties or liabilities of a director of Crown Melbourne. In particular, he will owe no fiduciary duty to the company, to Crown Resorts, as its group holding company, or to the listed company’s shareholders. This asymmetry is possibly unique in a solvent Australian company.

Aside from fiduciary duty, it appears that the special manager will not be at risk of incurring any vicarious liability either. Directors of Australian companies can be held personally liable for breaches of the law by the companies they govern, particularly in areas such as consumer protection, occupational health and safety, taxation, superannuation and environmental protection. The scheme of the Bill is to either absolve the manager of liability for anything done under the statute or attach that liability to the State if it arises under other legislation.

The power of the special manager to give a binding direction to Crown Melbourne is limited to certain defined circumstances, though he has a general power to give a direction substituting his judgement for that of the Board if he believes that the direction is in the “best interests” of the company or its casino operations. This has the potential to bring into sharper focus the asymmetry previously alluded to.

The special manager’s attention will be on the discharge of his functions, as detailed in both legislation and his instrument of appointment. His interest in commercial aspects of the business will likely be limited to matters which might threaten non-compliance with the law, or regulatory requirements. He will certainly not be driven by any imperative to maximize earnings, compete more aggressively for business or build shareholder value, other than by removing the stain of Finkelstein’s finding of unsuitability within his two-year term. It might be expected that if he is to err in judging what is in the best interests of the company, it will be on the conservative or lower-risk side.

The special manager’s attention will be on the discharge of his functions, as detailed in both legislation and his instrument of appointment. His interest in commercial aspects of the business will likely be limited to matters which might threaten non-compliance with the law, or regulatory requirements. He will certainly not be driven by any imperative to maximize earnings, compete more aggressively for business or build shareholder value, other than by removing the stain of Finkelstein’s finding of unsuitability within his two-year term. It might be expected that if he is to err in judging what is in the best interests of the company, it will be on the conservative or lower-risk side.

How might this affect Crown Melbourne’s business? For example, and without being too fanciful, it may require a complete reset of the company’s approach to the issue of gambling harm minimization. Its self-proclaimed “world’s best approach” to problem gambling was found by Finkelstein to be at odds with reality. A reset could conceivably impact the company’s advertising and promotional activities, see a wind-back of high limit slots and necessitate a fundamental rethink of its customer loyalty program. If the Board can’t be persuaded of the need for such changes, it would arguably be competent for the manager to simply direct the Board to implement suitably revised policies on the ground that the best interests of the company would be served by so doing.

The substitution of the special manager’s judgement for that of the Board has another dimension, which the Bill does not appear to address. While the company’s directors will be bound to comply with any direction they receive from the manager, they are not shielded or indemnified by law in the event that they are sued by any third party adversely impacted by implementation of the direction. The only workarounds are either the company’s own Directors and Officers Insurance Policy or joining the State as a co-defendant in any court proceedings. A more satisfactory approach would simply be to provide a statutory protection against third party action for the Board when implementing any directions it may receive.

The substitution of the special manager’s judgement for that of the Board has another dimension, which the Bill does not appear to address. While the company’s directors will be bound to comply with any direction they receive from the manager, they are not shielded or indemnified by law in the event that they are sued by any third party adversely impacted by implementation of the direction. The only workarounds are either the company’s own Directors and Officers Insurance Policy or joining the State as a co-defendant in any court proceedings. A more satisfactory approach would simply be to provide a statutory protection against third party action for the Board when implementing any directions it may receive.