In the second and final part of our deep dive into Macau’s junket industry, IAG Managing Editor Ben Blaschke looks at how VIP rooms work and examines why growing pressures on the VIP sector have encouraged many larger junkets to diversify their income streams (Click here to read Part 1).

”Macau’s VIP glory days are long gone,” says Alidad Tash, Managing Director of Hong Kong-based gaming consultancy firm 2NT8 Ltd.

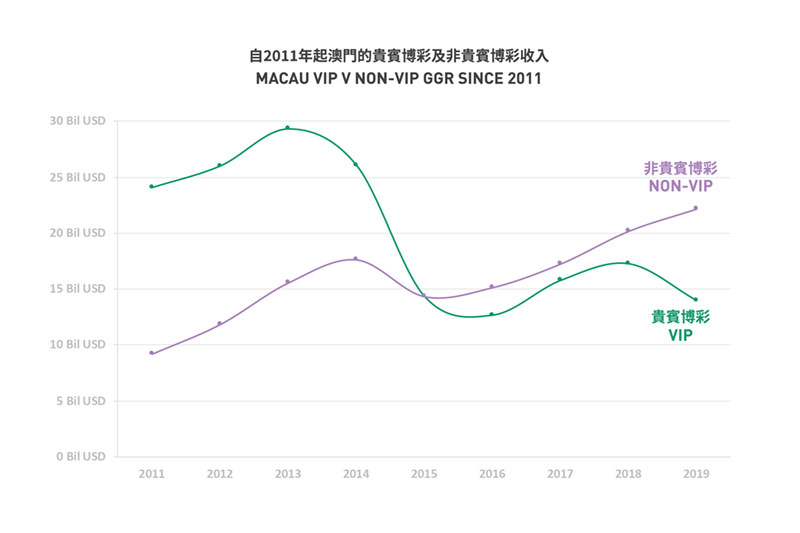

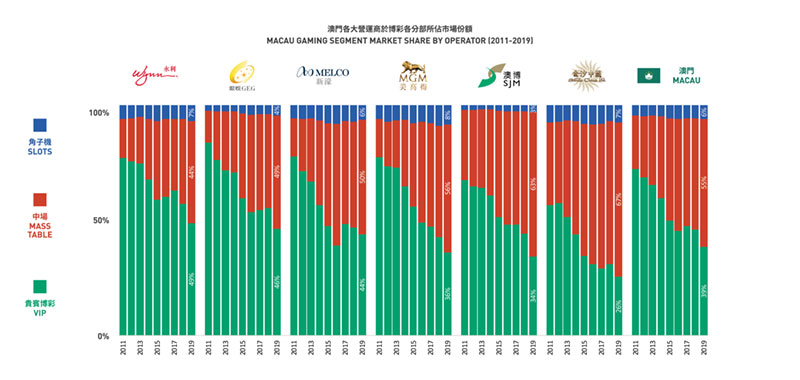

Once the kings of the castle when it came to Macau’s soaring casino industry, VIP operators today find themselves facing challenges they could never have dreamed of just a few short years ago. From a contribution to Macau’s gross gaming revenue of 72.9% in 2011 – previously as high as 77.2% in 2002 – and an all-time record in actual GGR of US$29.33 billion in 2013, the VIP segment kicked in a more subdued 38.7% contribution in 2019, with GGR of US$14.0 billion – less than half that of its halcyon days (Note: These are based on figures reported by operators, as opposed to those published by the DICJ, which suggest a 46.1% contribution last year).

“VIP doesn’t run the show anymore,” Tash continues. “There was a time when junkets could basically ask for whatever they wanted from operators, but the balance of power has shifted and it is now the operators squeezing the junkets by demanding that they prove their value.”

“VIP doesn’t run the show anymore,” Tash continues. “There was a time when junkets could basically ask for whatever they wanted from operators, but the balance of power has shifted and it is now the operators squeezing the junkets by demanding that they prove their value.”

China’s ongoing efforts to curb capital flow, the slowing of China’s economic growth and tighter regulations governing junket operations have all impacted the VIP segment, and junkets in particular.

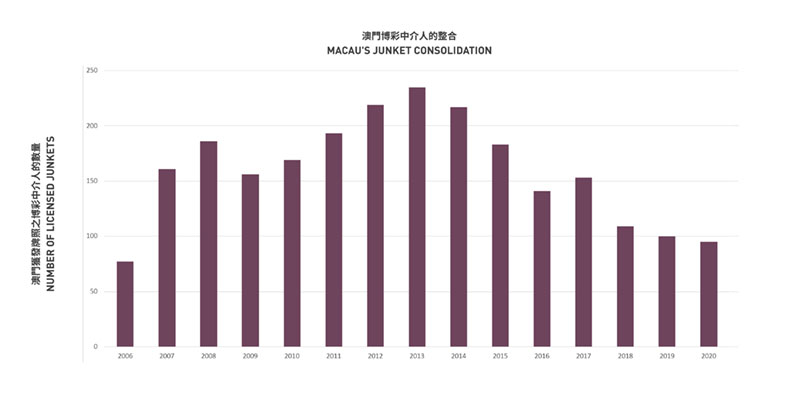

Yet what some are calling the slow death of the VIP sector might better be described as an evolution of sorts, highlighted by a pattern of consolidation within the junket industry over the past seven years and diversification into new revenue streams by the strongest of the survivors.

At its peak in 2013, Macau’s gaming regulator – the Gaming Inspection and Coordination Bureau (DICJ) – licensed 235 different junket operators but that number has fallen in all but one year since, dropping to a low of 95 in 2020.

At its peak in 2013, Macau’s gaming regulator – the Gaming Inspection and Coordination Bureau (DICJ) – licensed 235 different junket operators but that number has fallen in all but one year since, dropping to a low of 95 in 2020.

Conversely, the “Big 3” junkets – Suncity Group, Guangdong Group and Tak Chun Group – have gotten progressively bigger with Suncity estimated to now hold around 45% market share Macau-wide.

Suncity and Guangdong have also been the most proactive when it comes to diversification, with both having listed their non-junket operations on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange.

Suncity Group’s listed arm, operating under the same name, has interests in real estate in mainland China and luxury travel, and is the vehicle by which the company has spread its wings into casino operations in Vietnam, Russia and the Philippines. Rich Goldman Holdings, Guangdong’s listed arm, runs hotels and provides money-lending services in Hong Kong.

They are, experts say, both a means of legitimization, of accessing capital markets and, in the case of Suncity at least, of almost certainly aiding one of its ultimate long-game goals – taking part in the re-tendering process to become Macau’s seventh concessionaire.

Why would the biggest junket in Asia want to move into casino operations? It all comes down to the math.

HOW VIP ROOMS WORK

HOW VIP ROOMS WORK

As detailed in Part 1 of this article in the September 2020 issue of Inside Asian Gaming, junkets progressively moved off the streets and into the glitzy VIP rooms of Macau’s integrated resorts during the early 2000s – kickstarted by Macau gaming law 16/2001 and Administrative Regulation 6/2002, which outlined specific requirements for the operation of VIP gaming promotors.

Such moves were complete following implementation of the Gaming Credit Law in 2004, which for the first time allowed for concessionaires and junkets to provide credit to players and to legally enforce debt finance. This provided legal reinforcement and legitimacy to the long-term relationship between the two.

In 2009, the Gaming Promoters Commissions Regulation 27/2009 established a 1.25% cap on commissions that could be paid to gaming promoters on rolling chip sales. That 1.25% cap on commission rates is now standard in VIP rooms across Macau.

While junkets continue to offer a valuable service to operators given their ability to source high yield players, their existence within an IR’s walls have come with increasingly strict requirements over and above those required by Macau’s gaming laws.

There are, under a standard gaming promotion agreement between junket and operator, up to three means by which the junket may be able to generate revenue. The first is commission, offered in most cases by the operator at a steeped rate and capped at 1.25% of rolling chip volume.

Rolling chip volume applies only to those chips put into physical play at the tables as opposed to all chips purchased by the player from his junket or agent, and only on losing bets.

It’s important to note that, against the theoretical win rate of 2.85% on baccarat in Macau, commission of 1.25% on rolling is equal to 43.9% of the revenue generated within that room – representing a sizeable chunk of GGR.

It’s important to note that, against the theoretical win rate of 2.85% on baccarat in Macau, commission of 1.25% on rolling is equal to 43.9% of the revenue generated within that room – representing a sizeable chunk of GGR.

Generally, the junket will only pocket its 1.25% commission if they have brought the player in themselves. If introduced by an agent, most if not all of the commission will be passed directly to that agent, who may in turn give some money back to their player by way of rebates. Any agreements between the player and the agent are outside the scope of the junket itself.

Notably, while Macau has capped commissions at 1.25%, many neighboring jurisdictions such as Cambodia and the Philippines offer regulatory regimes that allow for higher commissions to be paid to junkets due to much lower gaming taxes. As a result, both junkets and their agents have demonstrated a greater propensity to take their players abroad in recent years which has in turn driven strong VIP growth in jurisdictions such as Cambodia and the Philippines. A ban on proxy betting in Macau combined with its stronger regulatory requirements also make some other jurisdictions an attractive proposition for many of these gaming promoters.

The second revenue driver for junkets in gaming promotion agreements is revenue share. More common than the commission model, revenue share agreements are usually favored by the larger junkets – particularly since the introduction of the 1.25% cap on commissions in 2009.

Revenue share agreements typically split GGR roughly 60-40 in favor of the operator, although the operator is also liable to pay the entirety of Macau’s 39% gaming tax which is applied to 100% of revenue generated – before the junket’s share is removed.

It is for this reason that junket play offers such low margin for operators. By the time they take out 39% tax, up to 44% in revenue share or commission and pay their operating costs – dealers, security, power bills to name just a few – their junket room margin works out somewhere in the vicinity of 10%. By contrast, operator margin in premium direct play (where operators source players themselves) is around 40% because, while the operator may provide some comps by way of hotel rooms or player points, it doesn’t have to share any revenue with a junket.

The decision on whether a gaming promotions agreement is commission based or revenue share based ultimately comes down to discussions between each junket and operator. The only real difference between the two is risk – under a revenue share model, junkets take a percentage of the risk on any losses incurred. Naturally, and quite contrary to the famous phrase “The house always wins,” losing days aren’t at all uncommon.

Of course the larger gaming promoters such as Suncity Group, Guangdong Group and Tak Chun Group have more bargaining power than their smaller peers when it comes to the percentage of profit they can demand, as well as the size and quality of their VIP rooms.

Finally, VIP promoters may also have certain bonuses written into their agreements that will reward them for exceeding their monthly minimum roll requirements. More on these minimums later.

Also working in the junkets’ favor is the fact that they have few fixed expenses when it comes to their VIP rooms. The operator is responsible for supplying all gaming staff including dealers, supervisors and pit managers as well as managing the tables and covering the cost of renovating rooms when it is felt they need updating.

The junkets may provide their own hosts as well as runners who go back and forth between the cage and tables to buy and redeem chips on behalf of their players. No such transactions are allowed at the tables themselves.

VIP rooms in Macau range from just a couple of tables in size to well over 20 for the big boys.

IMPACT OF MACAU’S TABLE CAP

In 2010, the Macau government announced the implementation of a table cap aimed at limiting the number of new live dealer tables allowed into the market for a period of 10 years from 4Q12 to the end of 2022. The cap allows for a 3% compound annual growth rate in the number of tables Macau-wide, meaning that from a base of 5,500 tables in 2012 there can be no more than 7,392 tables at the end of the 10-year period. As of 30 June 2020 there were 5,869 operational gaming tables in Macau, down from 6,739 at the end of 2019 on COVID-19 restrictions, according to official DICJ figures.

Prior to the implementation of the table cap in 2012, there was essentially no limit to the number of tables an operator would provide their junket partners. The general attitude at the time was the more the merrier.

The table cap changed all of that, forcing operators to make sure they were getting the most bang for their buck from the limited number of tables in their possession. And it has been VIP that has felt the pinch.

To understand why, imagine a scenario in which a baccarat table in a typical Macau junket room is generating daily roll of US$3.5 million. At the theoretical win rate of 2.85%, that’s a win of around US$100,000 per day. However, taking into account the 10% EBITDA profit margin for operators in Macau’s VIP segment, daily operator EBITDA for a table rolling US$3.5 million is just US$10,000.

Compare that to a mass table that wins US$50,000 per day but generates operator EBITDA of US$20,000 due to its much higher 40% margin. That’s double the EBITDA of a VIP table at half the win, and a much more attractive proposition for any operator.

It was with this in mind that operators first introduced minimum monthly roll requirements.

“It was a way to mitigate the fact that some junkets, back in the old days before there was a table cap, used to consume 10, 15 or 20 tables in a room and now because of the table cap, every table is precious,” says Tash, who was SVP of Gaming Operation & Strategy for Melco-Crown when the table cap was introduced. “Mass needed those tables back, so this was a means of cracking down on underperforming junkets.

“The opportunity cost of VIP tables varies by casino. Some casinos may achieve higher returns by removing some or all tables from underperforming junkets, and either converting them to better-margin mass tables, or transferring them to better-performing junkets.”

According to people within the industry who spoke with IAG on condition of anonymity, monthly roll minimums can be implemented as flat dollar amounts or in some cases by way of multipliers, whereby junkets are required to roll 20 times the amount of credit issued by the operator. For example, if credit of HK$50 million was provided, the operator would deem anything less than HK$1 billion in rolling to be underperforming. In such a scenario, the likely response would be a reduction in credit, reduction in tables, or both.

CONSOLIDATION, DIVERSIFICATION

Since the peak of Macau’s junket industry in 2013, when the DICJ licensed 235 gaming promoters to provide services to the SAR’s casinos, the trend has been rapid consolidation.

With fewer resources than the more established promoters and weighed down by the economic impact of China’s anti-graft campaign – launched by Chinese President Xi Jinping in 2012 but making its presence felt in 2014 – many smaller junket operators either folded or were swallowed up by their much larger rivals.

Others have been evicted by operators for failure to comply with tightening regulatory and AML requirements, while some have survived only by doing deals with the likes of Suncity, who may let them utilize tables inside their luxury VIP rooms in return for a cut of the profits.

Nevertheless, the number of licensed junkets has continued to fall, dropping below 200 in 2015 and below 100 in January of this year to the current 95. Experts predict that number will edge closer to 50 in the coming years.

It is with such external pressures in mind that savvy junkets have begun diversifying their revenue streams, tempering their risk from the highly volatile VIP business while at the same time distancing themselves from the industry’s colorful past.

“It has taken years to resolve itself to this point now where the industry has consolidated and regulation has progressively gotten just a little bit firmer,” offers David Green, a former gaming regulator in Australia and consultant to the Macau SAR Government.

“Now some of the big operators like Suncity and Tak Chun are really migrating away from just being focused on junket operations to either becoming casino operators themselves or diversifying completely.

“In the case of [Suncity Group CEO] Alvin Chau, he has gone into real estate and horse breeding and movies and all sorts of things. It’s given them a platform where they’ve been able to legitimize themselves while still maintaining the essential cash flow of their VIP ops.”

With one eye on 2022 – the year the Macau SAR Government is scheduled to put Macau gaming licenses out to tender following expiration of the six current gaming concessions and sub-concessions – Suncity completed a backdoor listing on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange in 2011 via its new listed entity, Sun Century Group Ltd, later changed to Suncity Group Holdings Ltd in 2017.

The listed entity (ticker code 1383) develops and leases property in mainland China ranging from residential and office towers to shopping malls, and operates a travel agency for high-end clients by which it provides luxury accommodation, transportation, concert tickets and restaurant reservations.

More recently, 1383 has made its casino operation ambitions abundantly clear. Alongside local firm VinaCapital and Hong Kong’s VMS Investment Group (associated with Chow Tai Fook), Suncity now owns 34% of integrated resort Hoiana, located in central Vietnam, which held its soft opening in June. The US$1 billion first phase spans more than 165 hectares and includes a casino, restaurants, an 18-hole golf course and more than 1,000 hotel rooms. When complete, the investment in Hoiana will total around US$4 billion.

Suncity also holds a 24.74% stake, soon to become almost 70%, in Summit Ascent Holdings, which in turn owns 60% of Russian casino-resort Tigre de Cristal in Vladivostok.

And the company announced late last year that it will develop a US$700 million casino and hotel component of Manila’s Westside City Resorts World – a new multi-billion-dollar leisure and entertainment township linked to Resorts World Manila operator Travellers International Hotel Group Inc.

Guangdong Group, formerly known as Neptune Group and Neptune/Guangdong, has connections to Hong Kong-listed Rich Goldman Holdings, which changed its name from Neptune Group Ltd in 2017. The company stated at the time that, “the current name of the company does not reflect the diversity of businesses conducted by the group. While the group is still engaged in its gaming business by receiving profit streams from junket operators, the group now focuses more on its money lending business and management and operation of hotel business.”

Describing itself as an investor in junket rooms as opposed to actually conducting junket operations like Guangdong Group, Rich Goldman severed ties with its last remaining Macau junket room, located at Grand Lisboa, in March although it has since revealed plans to invest in a room at Manila’s Solaire Resort & Casino.

The company is actively involved in money lending, while in March 2019 it acquired boutique Harbour Bay Hotel in Hong Kong’s Tsim Tsa Tsui.

The remaining member of Macau’s “Big 3” junkets, Tak Chun Group, has no direct ties to a listed entity but its CEO, Levo Chan, has been active in recent weeks – outlaying US$165 million of his own money to acquire a 20.65% stake in Macau Legend Development Ltd. At time of writing he was due to make a mandatory cash offer for the rest of the company’s publicly held shares that could see him own almost 50% of Macau Legend by November.

Macau Legend controls the Macau Fisherman’s Wharf precinct, including Legend Palace and Babylon – both operating casinos under license from SJM. It also owns Savan Legend in Laos and a shopping complex in Hengqin.

OMINOUS OUTLOOK

Opinion remains divided over the long-term outlook for Macau’s junket industry.

“Macau in 5 to 10 years down the line will be far less reliant on VIP – and that’s a good thing,” says Tash, who supports operators placing more focus on its higher-margin mass segments in the coming years.

Others still consider VIP, be it junket-led or direct, to be an important tool in steering Macau towards quality of visitation over quantity.

Either way, there are undoubtedly going to be short-term challenges as the gaming industry starts the long road back from COVID-19 – a road not helped by China’s latest crackdown on gambling-related capital outflow.

According to Credit Suisse analysts Kenneth Fong, Lok Kan Chan and Rebecca Law, the VIP system will “substantially scale down over the next few years, dragging the pace of recovery,” as a result of the crackdown.

They add, “Unlike in 2010-14, when the central government had targeted corruption, this time around, Beijing is targeting gambling activities. This hurts big players demand, affects junket debt collection, and blocks funding channel for big players. According to the State Council Information Office, it could be a three-year campaign until 2022.”

Although Beijing’s regulatory tightening on gambling activities and capital outflow is aimed more at maintaining China’s financial stability than specifically targeting Macau, the analysts noted recent reports that some big players had been stopped at the border and asked to declare they would not gamble while in Macau, placing a significant burden on demand.

However, this can act as a long-term positive for the more resilient junkets according to former government advisor Green, helping “the large operators get larger and the small ones to progressively disappear.”

It will also aid efforts for the industry to legitimize. “The ones that we’ve seen disappear over the past few years have generally been the ones breaking the rules anyway,” says Niall Murray, Chairman of IR consultancy firm Murray International Group.

It will also aid efforts for the industry to legitimize. “The ones that we’ve seen disappear over the past few years have generally been the ones breaking the rules anyway,” says Niall Murray, Chairman of IR consultancy firm Murray International Group.

“They’ve either folded or been rolled into a group that they can work with. That’s one of the main reasons for consolidation. The good agents are still around, having either merged to form new alliances or come in as sub-agents under the bigger junkets. And Suncity has done that better than the rest.

“From what we had to clean up 20 years ago to where we are now, there is a world of difference. It’s much better.

“Is it perfect? No. They’re not putting in the same strict regulations as they are in Singapore where you may as well say goodbye to the VIP business.

“But there is a long history of junkets that has built up over time. They are moving with the times, becoming more legitimate, it’s improving with each passing month and I take my hat off to them.”

WHO’S WHO IN THE ZOO

SUNCITY GROUP

One of Macau’s longest running VIP gaming promoters, Suncity Group has also emerged from the pack over the past decade to become widely acknowledged as the SAR’s largest junket with an estimated 45% market share.

Suncity operates 16 VIP clubs Macau-wide as well as nine other clubs in the Philippines, Cambodia, Vietnam and Korea.

To give an idea as to the full financial clout of Suncity Group, IAG has been informed that, before COVID-19, the company would regularly have upwards of HK$1 billion deposited with most of Macau’s major IR operators.

In response to recent rumors that Suncity was facing a cash shortage due to pressures brought about by COVID-19, CEO Alvin Chau revealed evidence to the contrary in July of this year via a public statement in which he provided images of Suncity Group bank statements. They showed that Suncity VIP Club recognized at the time a total amount of fiscal reserve of HK$10.58 billion (US$1.36 billion) and had “cash flows in cage” to be used in the daily operation of the Suncity VIP Club of HK$18.6 billion (US$2.40 billion). It also had total deposits of HK$16.5 billion (US$2.13 billion) in two Macau banks.

Away from gaming, Suncity’s listed arm operates three key subsidiaries – Sun Entertainment Culture, Sun Travel and Sun Food and Beverage – supporting the travel and leisure pursuits of its high-end clients.

Established in 2011, Sun Entertainment Culture is involved in the production, planning and management of films, concerts and exhibitions with a catalogue boasting more than 65 films under its belt.

Sun Travel describes itself as an “all-round service platform for global tourism” offering tailor-made trips for its guests to locations around the world, while Sun Food and Beverage operates eight restaurants in Macau and another eight in Chengdu and Chongqing, mainland China.

GUANGDONG GROUP

Formerly known as Neptune/Guangdong Group before dropping the Neptune element from its title in recent years, Guangdong Group is another of the “original” junket operators to have transitioned from the industry’s “colorful” formative years to the more professional models that inhabit today’s IRs, and flourished in doing so.

Depending on who you speak to – the company has far greater exposure to some concessionaires than others – Guangdong represents anywhere between 10% and 18% of Macau’s junket market, making it a clear number two behind Suncity. The company operates 10 VIP clubs in Macau, evenly spread between Cotai and the Macau peninsula.

TAK CHUN GROUP

Founded in 2007, Tak Chun Group has rapidly grown to become one of the leading operators in Macau’s VIP gaming space with an estimated market share somewhere in the realm of 10% to 12%.

With a workforce of around 1,100 staff, it runs 16 VIP Clubs across Macau as well as operations in Vietnam and Cambodia.

The company tells Inside Asian Gaming that its “new-found vision is to reach out globally and beyond industrial boundaries to become a distinguished world-class enterprise of entertainment varieties.”

This includes the organization of trips for its VIP guests to “Korea, the Philippines, Singapore, Vietnam, Australia, United States of America, United Kingdom, New Zealand, Cambodia, Malaysia, Russia, Saipan, as well as destinations operated by Dream Cruises (owned by Genting Hong Kong), and seamlessly looking after all arrangement of accommodation, dining, entertainment, and transportation.”

Tak Chun is also involved in real estate across Asia, primarily via investments in residential developments, and owns a luxury watch business, Sio Fung Lin Watches Group.

GOLDEN GROUP

Rarely mentioned among Macau’s big junket hitters these days is Golden Group, a junket closely linked with SJM Holdings and its predecessor, STDM. Founded in 1990, its ownership group includes Angela Leong – the fourth wife of STDM founder Stanley Ho and current Co-Chairman and Executive Director of SJM Holdings – and Li Chi Keung, Managing Director of Macau Jockey Club and financier of several Macau casino operations.

Publicly at least, Golden Group has downsized considerably in recent years – from 11 VIP Clubs in 2015 to just five remaining as of June 2020 when the company announced the closure of its three VIP Clubs at Casino Lisboa. Those closures also represented the end of an era for Lisboa, the birthplace of Macau’s modern-day junket industry (see Part 1 of this article in the September issue of IAG).

Golden Group has five remaining VIP Clubs – all of them located at neighboring Grand Lisboa – although the company is expected to open rooms at SJM’s new Cotai resort, Grand Lisboa Palace, once it opens in December.

While not as prominent as other junkets in Macau, IAG has heard from sources that Golden Group in fact turns over as much, if not more, than almost all of its competitors in the market.

“They laugh when people talk about Macau’s ‘Big 3’ junkets,” one source said.