MdME lawyer Carlos Eduardo Coelho takes a critical look at a proposed amendment to Macau’s gaming law that would see many casino employees banned from entering any Macau gaming floor outside of work hours.

In September, Macau celebrated 10 years of Responsible Gambling (RG) promotion. The event was dubbed by Professor Davis Fong, the man overseeing the Institute for the Study of Commercial Gaming of the Macau University (ISCG) – possibly the public body most embedded in the task of addressing RG policies – as a “very important landmark” for Macau. And indeed it was! Since November 2008, when then Chief Executive Dr Edmund Ho announced that the government would prepare RG guidelines in accordance with international standards, a lot of water has passed under the bridge.

If we look at the numbers, based on the Responsible Gambling Awareness Survey prepared by ISCG in December 2017 (RGAR Survey), before RG policies and practices were put in place in 2009 “only 16.2% of Macau residents were aware of responsible gambling. This awareness rate then gradually increased to 63.7% in 2017.” These results can only mean a lot has been done in a short period of time.

RG normally refers to policies and practices designed and aimed at preventing and reducing potential harms associated with gambling. According to the Department of Justice and Attorney-General, Queensland, Australia (2015), RG refers to “The provision of safe, socially responsible and supportive gambling environments where the potential for harm associated with gambling is minimized and people can make informed decisions about their participation in gambling.”

Under ISCG, “Responsible Gambling is a practice that confines the gambling-related damage to a socially acceptable level.” When talking about RG policy framework, it must always consider harm minimization measures addressed at reducing the number of players with a gambling disorder or limiting respective gambling activity. No less importantly, it should also consider the principle of informed choice (or informed decision) and the right of an individual to choose whether or not to participate in gambling activities (which may be achieved by promoting consumer and community awareness and education).

Under ISCG, “Responsible Gambling is a practice that confines the gambling-related damage to a socially acceptable level.” When talking about RG policy framework, it must always consider harm minimization measures addressed at reducing the number of players with a gambling disorder or limiting respective gambling activity. No less importantly, it should also consider the principle of informed choice (or informed decision) and the right of an individual to choose whether or not to participate in gambling activities (which may be achieved by promoting consumer and community awareness and education).

Given the fast-paced growth of the gaming industry and its increasing international visibility, Macau stakeholders – Government; Gaming Operators; Gamblers and respective families; Education and Other Community Organizations; and Gambling Disorder Prevention and Treatment Centers – had no choice but to step on the reform pedal and start pushing forward for an RG framework.

That indeed happened. Several laws and measures related with RG were introduced for the first time to the gaming industry: in November 2012, Law no. 10/2012 established the legal framework of the conditions for entering, working in and gaming at casinos, by (i) raising the minimum age to enter the casinos to 21; (ii) providing for a self-exclusion and a third party exclusion program; (iii) addressing the treatment of winnings of people not allowed in casinos. Guidelines for internal implementation of RG by the operators were issued by Macau’s gaming regulator, the Gaming Inspection and Coordination Bureau (DICJ). Several public entities have held a series of “Responsible Gambling Awareness” activities and initiatives. Interdepartmental taskforces were put in place. A “Central Registry System of Problem Gamblers” has been set up.

Most of the measures put in place were a necessity. However, the same cannot be said about the amendments in the pipeline to Law no. 10/2012, the first reading of which was recently approved, and to Law no. 5/2011 (Smoking Law). Amongst the proposed amendments to Law 10/2012, one in particular raised the eyebrows of many in the industry. We refer to the proposal for a full ban on casino entry (with very limited exceptions) for gaming concessionaires’ workers.

Based on the first reading of the law (which we note is still under discussion in the Legislative Assembly and may undergo further amendments), gaming concessionaires’ workers who provide respective services within the casino premises including, but not limited to, table games, gaming machines, cashiers, public relations, F&B, cleaning, security and surveillance shall be banned from entering any casino premises (not only those operated by respective employers) outside working hours. The underlying reason for this ban (which is based on data collected from 2011 until 2016) is that the majority of individuals affected by gambling problems are dealers or other workers from the gaming sector. Therefore, their protection should be reinforced.

Based on the first reading of the law (which we note is still under discussion in the Legislative Assembly and may undergo further amendments), gaming concessionaires’ workers who provide respective services within the casino premises including, but not limited to, table games, gaming machines, cashiers, public relations, F&B, cleaning, security and surveillance shall be banned from entering any casino premises (not only those operated by respective employers) outside working hours. The underlying reason for this ban (which is based on data collected from 2011 until 2016) is that the majority of individuals affected by gambling problems are dealers or other workers from the gaming sector. Therefore, their protection should be reinforced.

But we see no reason for this amendment. Although understanding the underlying concerns and even assuming (based on known studies) that casino employees, because of their full access and exposure to gambling, may have higher levels of gambling related problems, the suggested amendment goes too far and is probably not the correct way of addressing that concern.

The data collected is, in our view, insufficient – it does not clearly show the number of casino employees (other than dealers¹) who are indeed affected by a gambling disorder – and the most recent data seems to point in a different direction.

Going back to the RGAR Survey, one of the conclusions is that “Gaming employees (90.8%) continued to have significantly higher level of awareness of responsible gambling than non-gaming employees (57.8%). In this study, gaming employees were found to have better understanding of casino gambling. Besides, gaming employees … were more generally aware of the government’s responsible gambling policies and regulations.”²

Why shouldn’t employees of the noodle corner inside the gaming floor be allowed to enter a casino outside of working hours? And why not be able to gamble? And how is the enforcement going to be made? How to control those employees’ work schedules? Why is the law assuming, or presuming, that such an employee is more prone to have a gambling disorder than a lawyer such as myself who works for this industry?

Any unjustified intrusion or limitation to one’s personal freedom should be very well justified as it contends with a fundamental right specifically provided for under Macau Basic Law. Instead of imposing a harmminimization measure – full entry ban – the focus should continue to be directed onto awareness and training. Informed choice should prevail and the casino employees should retain the ability to decide whether and how they intend to gamble.

The smoking ban, not being a harmminimization measure but rather a measure of public health, is used by governments in several jurisdictions to complement RG policies. Following a first, very restrictive approach where smoking was not allowed on main gaming floors but only in specific areas (VIP rooms included), from 1 January 2019 a full smoking ban will be enacted within casinos except for approved smoking lounges (where gambling is forbidden). Macau shouldn’t be so hard on itself! It has been a good RG student and does not need to push the threshold of its RG policies to the limits. It’s a rule of thumb within this industry that, from the moment any RG limitation is put forward, it is highly unlikely to ever be reversed. Despite our criticism above, Macau (and its stakeholders) should be well aware of what has been achieved in such a short period of time. Even though there is still a long way to go, RG is a reality within the territory and it is here to stay. Now it is time for the policies to focus outside.

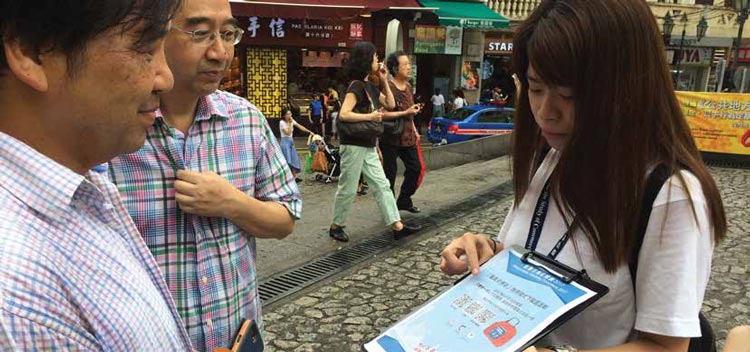

As Professor Davis Fong very recently stated, “Helping tourists who may need assistance in fighting gambling addiction is now a key focus of the government.” It is now time to slowly shift the RG policy focus from the Macau resident to the real customer of our casinos – the mainland China player. Since more than 80% of Macau visitors are from the mainland and given that Macau is an integrated part of China, it cannot wash its hands and simply “export” its gambling disorder individuals and their associated problems. Macau should aim high in terms of RG, should be a beacon and an example to be followed, especially throughout the emerging gaming markets within Asia.

As Professor Davis Fong very recently stated, “Helping tourists who may need assistance in fighting gambling addiction is now a key focus of the government.” It is now time to slowly shift the RG policy focus from the Macau resident to the real customer of our casinos – the mainland China player. Since more than 80% of Macau visitors are from the mainland and given that Macau is an integrated part of China, it cannot wash its hands and simply “export” its gambling disorder individuals and their associated problems. Macau should aim high in terms of RG, should be a beacon and an example to be followed, especially throughout the emerging gaming markets within Asia.

It is in a special position to understand and study its customer – the Chinese gambler – and their respective idiosyncrasies and to create its own set of rules (why not an RG Code of Conduct; why not RG taught in schools; why not a wider focus on corporate social responsibility measures?), bearing in mind all the specificities of its gaming sector rather than just following international directives.

Such directives may be important as minimum standards of guarantee and prevention but they cannot take the place of a more profound reflection by Macau stakeholders on its own reality and its own particular set of problems.

1 According to the Central Registry System of Problem Gamblers 2017 Annual Report Summary, from the total number of individuals requesting assistance in 2017 due to Gambling Disorder, more than 10% were casino dealers, there being no specific reference to any other kind of casino worker request for assistance.

2 We note however that RGAR Survey points out that gaming employees’ knowledge on gambling disorder has still to be improved.