In sending marketing messages to mainland Chinese, Macau casinos generally make the mistake of assuming all Chinese have similar cultural attitudes and preferences. Casino marketing guru Octo Chang teams up with Ben Lee, VP-Casino Projects with the Diamond Casinos Group, and Macau tourism academic Glenn McCartney to point out the need to differentiate marketing messages in different parts of China

All Chinese look the same.” Many Caucasians – often apparently unprejudiced ones – are guilty of having uttered that statement on arriving in the Orient. The reverse is also true. A Chinese traveller landing in a predominantly Caucasian country for the first time can also have trouble distinguishing between individuals. Why is that so?

The answer lies in our respective backgrounds and the resultant filter we use to view the world.

If one grows up in a multi-hued society where the colour of the eyes and hair differ, as well as the colour of the skin, one would naturally select those as distinguishing features. If, on the other hand, one grows up in a society where the common physical traits are dark hair and brown eyes, one ends up looking for other facial features like shape of the eyebrows, shape of the eyelids or the face, skin tone, etc, to tell individuals apart, and ignoring what would seem to the Caucasian to be the most obvious distinguishing features.

Just as Caucasians may experience difficulty in distinguishing physical differences between individual Chinese, they may also fail to distinguish cultural differences. The various Chinese communities in this part of Asia have had divergent cultural evolutions, and the savvy international marketer understands they need to be approached differently. For example, the marketer may tailor different messages for the Chinese communities of Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, Vietnam, Philippines, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and last, but certainly not least, mainland China. The marketer may congratulate himself on his sensitivity in making the above distinction, but would still be making a huge mistake – namely, thinking that all mainland

Chinese are alike and can be considered a homogenous entity. Chinese themselves are guilty of such ignorance, and you will find examples of it in everyday life in Macau and neighbouring Hong Kong. An overseas-born Chinese friend who happened to speak a different dialect to the dominant Cantonese in Macau was told he couldn’t be Chinese if he didn’t speak Cantonese. That’s perhaps not surprising given that local schoolchildren in Macau and Hong Kong refer to the Cantonese dialect as “The Chinese Language.”

If it Works for Me…

This cultural arrogance has made its way into the marketing media, and Hong Kong-style promotions and slogans pervade the marketing efforts of all of Macau’s casinos, from US-based giants Sands and Wynn to smaller players like Rio and President. The mentality of “it works for me, then it must work for all the other Chinese,” neglects the myriad cultural differences among the different regions of China.

Some basic facts to consider – the population of Beijing is 12.8 million, Shanghai 20 million, Guangdong 84 million , Fujian 34 million, and so forth. These cities and provinces are bigger than most countries, and each have their own unique and continuously evolving dialect and cultural roots. Disregarding the written language, most of these dialects are considered unique languages by language professors.

In a recent survey conducted in the departure areas of various regional airports, research found that the messages that would influence the travellers to choose a destination differed consistently depending on the origin of the travellers. In particular, the survey found that the perception of Macau as a destination varied quite markedly among travellers from Hong Kong, Shanghai, Beijing and Taiwan.1

Macau gaming operators send out a barrage of messages across a multitude of media, yet according to the survey findings, a message that may be suited to one market segment may actually alienate another segment. For instance, Taiwanese travellers indicated that safety is an important criterion, but to emphasize it in a marketing communication to travellers from another market may instead raise questions as to why safety should even be an issue at all.

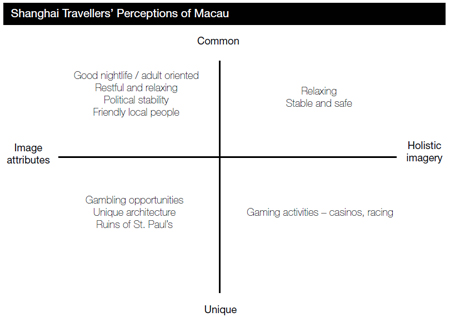

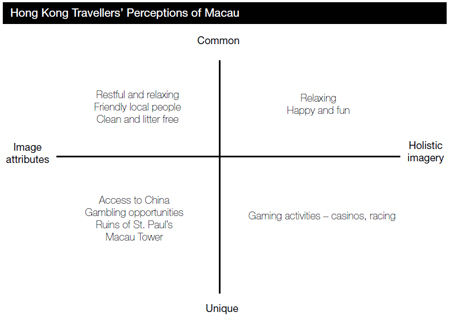

The following two graphs are examples of the leading image components of Macau in the mind of travellers from Hong Kong versus those from Shanghai. “Common” images are positive attributes also possessed by other destinations, while the “unique” images refer to attributes offered by Macau in particular, and generally absent in competing destinations

The two graphs show that both sets of travellers perceive Macau’s sole unique draw as – surprise, surprise – gaming, as seen in the bottom right-hand quadrant. Both also unsurprisingly associate the image of the historical Ruins of St Paul’s with Macau.

Shifting Perceptions

Now the challenge ahead for Macau operators is to alter travellers’ perceptions and align them with their product offerings: signature restaurants (Lisboa’s Joel Robuchon), glitzy nightlife (Wynn’s Tryst) and one-stop adult entertainment (Grand Waldo’s 5-storey “Entertainment Block”). That is, the operators have to create the perception that Macau is more than just a gambling haven in order to maximize the draw-cards they have put or are putting in place.

Apart from the perceptions, however, how can operators actually motivate travellers to come to Macau? It takes a two-pronged approach.

The first, as explained, is to change the current perception to match what you have in terms of attractions. The second strategy should actually precede the first, and that is, to provide those attractions which the travellers actually want to experience. Is the glitzy thousand-dollar-entry and girl- around-the-pole something that will draw a punter from Beijing? Does Joel mean anything to the Shanghainese, or is the glamour chef an attraction relevant only to Hong Kong elites?

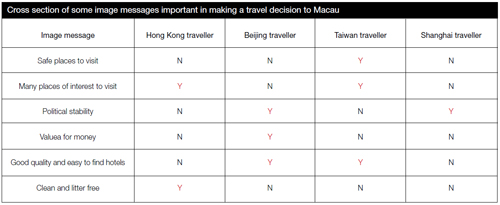

Just to highlight some differences, the analysis of the survey results also established the individual messages that were deemed by the travellers as important to them and that might influence their decision to travel to Macau in the future. The “Y”s represent factors that were deemed important, while the “N”s represent those that were not.

As mentioned earlier, the Taiwanese are rather concerned about safety in Macau and need to be reassured that the gang-wars preceding the handover to Chinese sovereignty in December 1999 are not likely to resurface. Hong Kong visitors, on the other hand, prefer a clean and tidy environment – something that does not even appear on the radar of the mainlanders.

Looking at the differences among the mainlanders themselves, it is interesting to note that the northerners consider good quality hotels a must, while the Shanghainese do not give a hoot. Likewise, neighbouring Hong Kongers do not need hotels, yet owing to restrictions on advertising gambling in Hong Kong, hotels are the featured element of the majority of casino ads over in Hong Kong.

Obviously, a “one message fits all” approach is not the most optimal in promoting travel to Macau. Focusing on casino-based tourism as the sole marketing and promotional strategy may also limit the appeal of Macau in the future to wider traveller markets.

With the exception of the Americans, just about all the other operators and casino owners in Macau come from Hong Kong, and their marketing promotions have a sameness about them. Although the Vegas newcomers offer different hardware and deploy subtler branding messages, they are also tending towards the same direction in terms of execution and tools.

Word of Mouth

The survey results also suggest that the value of each marketing method differs across markets. The Taiwanese traveller was being bombarded with TV and print advertisements and TV travel programmes – essentially your typical Hong Kong-style campaign. However, the Taiwanese surveyed indicated that they placed much greater importance on outdoor advertising, the internet and work colleagues.

In an earlier column, “Those Annoying People Called Customers,” that appeared in the October 2005 issue of Inside Asian Gaming, I made mention of a marketing case where the informal word of mouth advertising was the key element in the successful outcome. This appears to be the case here as well.

The sameness in execution I alluded to is clearly evident everywhere you go in Macau and Hong Kong. Print media galore, Canto popstars and movie celebrities, and the ubiquitous lucky draw are such common occurrences that one has to wonder about the ROI and measurable effectiveness of such tools.

This clearly shows that there is scope in places to greater align the communication mix, leading to a better use of marketing and promotional resources. It will be in the interpretation, implementation and placement that challenges will arise for the many Vegas-driven/ Hong Kong-centric casino marketing departments in Macau.

Ultimately, the product itself may have to be tailored more closely to individual market segments. How many times have you heard the credo that the mainland Chinese will spend all their money gambling, and will stay in the cheapest hotel or sometimes not stay in a hotel at all? Look at the Hong Kong (read Cantonese) lifestyle. Food is a brief respite from the normal schedule of making money, a stop to take in some fuel in order to keep going. Even wedding dinners in Hong Kong take only about 45 minutes (not including the mandatory 1-2 hour wait for everybody to turn up) from the cold platter to the Fried Rice.

On the other hand, residents of Beijing appear to have a much more sedentary lifestyle. The northerners will actually spend a couple of hours over dinner, talking and holding verbal discourse over whatever topic of the day may be current. Look at the speed of the pedestrians – in Hong Kong, any newcomer casually sauntering around the MTR risks being trampled by the passengers. In any of the other provinces north of Guangdong, the pace of life is definitely slower in most respects. It is considered a truism that mainlanders stay an average of only 1.2 days in Macau and spend all their money gambling at the expense of good food and entertainment. However, it could be that this stereotype only applies to the Hong Kong and Guangdong set (with Southern China having been heavily influenced by Hong Kong media anyway), who make up the bulk of visitor numbers to Macau and hence skew the average data.

On the micro level, this means that the operators will have to re-pitch their F&B outlets at different levels, and we are seeing that. Wynn Macau is now re-tuning its food outlets, which suggests it may not have learnt from the experience of Sands Macau. Meanwhile, Sands still does not know what to do with its outlets. Galaxy’s Starworld has done a little better by offering various forms of Chinese cuisine to the point where even the local Macanese are frequenting them on the weekends (the old informal network in play here).

At the macro level, the operators will have to rethink their main hall in terms of layout, positioning and perhaps the customer gaming experience. They will also have to conduct much more marketing research than has been done to date, in order to identify the various segments and the means to reach them.

At the moment, the product offering in the main halls of the larger casinos are uniform. This means that the smaller (individually owned) casinos, if let loose by SJM and Galaxy, have a potential distinct advantage over their larger brethren if they can reposition themselves to capture a specific niche market segment.

As table revenue becomes more diluted, the focus of future marketing efforts will tend towards identifying as many viable niche market segments as possible. In fact, we may even see small operations targeted at other parts of the region, such as a boutique Korean or Japanese casino-hotel (feelers and concepts are already being discussed).

Or maybe a spicy Sichuan or a Fujian style property complete with native speakers and cuisine? Why not? The population base is certainly there.

As the Northerners will tell you with a disdainful sniff – only the Southerners eat rice. Chinese are not all the same.

Octo Chang is the pseudonym of our Macau-based casino marketing columnist, who has extensive qualifications in the gaming industry. Please feel free to forward any amusing anecdotes or observations to ka.chng@gmail.com.

Ben Lee has an extensive background in casino marketing in Asia and Australia, particularly in profiling the Chinese market segment.

Glenn McCartney, PhD, is an Assistant Professor in Tourism at the Macau University of Science and Technology.

Notes

1 This research was commissioned by Glenn McCartney and conducted in the departure areas of airports in Beijing, Shanghai, Hong Kong and Kaoshung, as these destinations represent over 90% of air travel to Macau. Random sampling was between 300 to 450 travellers at each airport, and tested as valid. The questionnaire and survey was designed based on destination image and branding research undertaken globally in the last ten to fifteen years and data was tested using SPSS software and various multivariate techniques.

Why Chinese Like Gambling

While mainland Chinese cannot be considered a homogenous entity, they are widely considered to be the world’s most hard-core gamblers. CLSA’s Aaron Fischer looks at the origins of the Chinese passion for courting lady luck

Throughout history, the Chinese have been avid gamblers, betting on everything from cricket fights to archery contests. Gambling has been dubbed China’s ancient vice. In fact, the very first accounts of gambling, dating back some 3,000 years, were found in China. The history of Mahjong, one of the most popular Chinese gambling games, goes back to 960 AD – some even believe Confucius to be the inventor.

It is interesting to note that the Chinese love of gambling has persisted despite strict laws and bans imposed by imperial rulers and, more recently, the Communist Party. Not only were they considered morally bad (Confucius said that “a gentleman does not gamble”), gamblers were sentenced to death during the Song Dynasty and had their hands cut off during the Ming Dynasty. Gambling is, by and large, a way of life for the Chinese. Back in the late 1800s, historians in China and Hong Kong observed that everyone gambles for everything and that “the boys learned gambling as soon as they could talk, and pursued it through life.” Even buying bread from a street vendor can be a gambling game. Recent anecdotal evidence suggests the same still holds true centuries later.

The weekly TV show about the lottery had one of the highest ratings in Shanghai in 2001, according to Xinmin Evening News. It is estimated that Chinese gambling losses abroad (including Macau) amounted to over US$75 billion annually in recent years – almost half of Thailand’s annual GDP. Indeed, where else but in this region could one find a whole genre of film dedicated to stories about gambling masters?

This leads one to wonder why the Chinese love to gamble. Although no single explanation seems to fully shed light on this “gambling gene”, a few probable reasons have been proffered. The first is economic: throughout its long history, most Chinese people have been impoverished, so they naturally hope for a windfall from gambling games. The second is the supposed lack of a national game, or in other words, they have nothing better to do. The third, and more plausible explanation, is the deep-rooted belief in luck and pursuing good luck – a fundamental component of Chinese culture.

It is this strong belief in luck that leads many to gamble their meager savings in the hope of becoming rich. So a love of gambling can be said to follow naturally from this belief in luck.