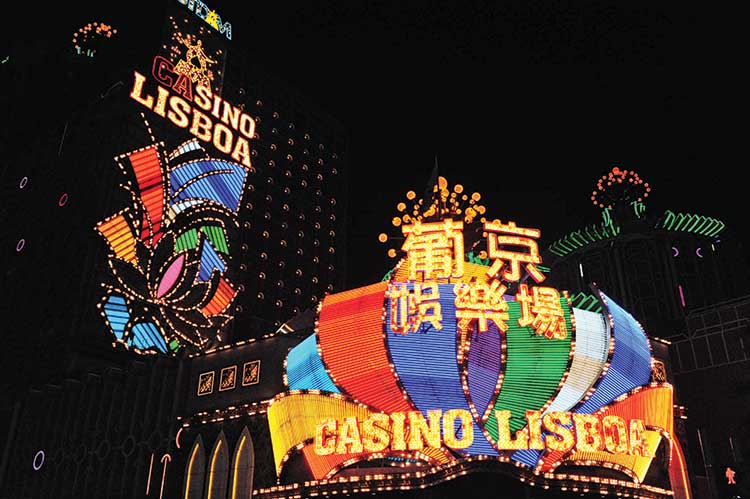

Former gaming regulator David Green explains why Macau’s regulatory model for the VIP Promotion, or “junket”, industry continues to be in the best interests of both the Macau SAR and the People’s Republic of China.

Perhaps enforced isolation is imbuing me with a distorted sense of time compression, but it seems some gaming industry experts continue to bang on in any forum that will hear them about the embedded weaknesses of Macau’s approach to the regulation of junket operations.

Their normative pronouncements about what constitutes good-practice regulation pay little to no regard whatsoever to history, context or relevant public interest. Rather, they would seem to promote the idea that there is a gold standard which implies contextual irrelevance, and that should be pursued irrespective of host jurisdictions’ public interest. Intellectual and cultural imperialism is alive and well. It shouldn’t be.

To understand why Macau’s regulatory regime for junkets has evolved as it has, it is necessary to go back to the Portuguese colonial era. Although Portuguese merchants had settled Macau in the mid-16th century, it was not until 1979 that Portugal established formal diplomatic relations with the PRC.

Portugal had relinquished control of its other colonies, such as Angola and Mozambique, after the military coup of April 1974, known as the Carnation Revolution. At the time, the PRC declined to take over the administration of Macau, perhaps because it was itself in the midst of the Cultural Revolution.

It was not until December 1999 that the handback was completed, some 12 years after the Sino-Portuguese declaration regarding the return of Macau to Chinese administration had been signed.

Upon its establishment, the administration of the inaugural Chief Executive, Edmund Ho Hau Wah, found itself on the proverbial horns of a dilemma. First, Macau’s traditional secondary industries of textiles and footwear, boat building, fishing and fireworks were all in decline. Secondly, Articles 104 and 105 of the Basic Law of Macau conferred financial independence on the SAR. This cut two ways; the PRC could not levy taxes or share in the SAR’s revenue streams, but equally, though implicitly, there was no obligation placed upon the PRC to shore up the finances of the nascent administration. Article 105 specifically required the SAR to adopt policies which would see revenues match or exceed public expenditure.

On the plus side of the ledger was Macau’s gaming industry. In 1999, tax on the gross gaming revenue of the monopoly operator, STDM, contributed 47% of all government revenue. STDM employed directly more than 10,000 people, or about 5% of the workforce at the time. This number does not include junket operators’ staff and agents, who were generating more than 60% of STDM’s revenue through their VIP operations. It is likely they were far more numerous than the direct employees of STDM.

In a report written for the US Congress in August 1999, the Congressional Research Service presciently observed that, “In dealing with Macau after December 20, 1999, China will face the dilemma of how to preserve the profitability of the gambling industry, in order to retain this significant source of revenue.”

The PRC was unlikely to provide a mechanism for the lawful recovery of gaming debts incurred by its residents, given the propensity for such recourse to contribute to social disharmony. Moreover, were it to do so, it would potentially make junket operators, their employees and agents redundant.

The perils associated with that course were demonstrated during the open warfare that had broken out in 1997 between the 14K and Sui Fong triads over control of VIP rooms in STDM’s casinos. Tourist arrivals, the source of much of the economy’s revenue, fell almost 20% between 1996 and 1998. It was in the interests of both the PRC and the Ho administration, and the people of Macau, that the potential of the gaming industry to be a driver of growth be stimulated.

Arthur Andersen was appointed in August 2000 to advise the SAR government on how to proceed with liberalization of the industry. The most obvious point to be made at the outset was that Macau needed to adopt a regulatory regime for the industry which would meet at least the minimum expectations and requirements of likely bidders for new concessions. The concession system itself was foreign to most bidders.

In October 2001, the omnibus gaming law, 16/2001, was adopted, and was closely followed by Regulation 6/2002, which provided for oversight of junket operators and their licensing. The regulation did not come into force until 2004; the delay was intended to give junkets the opportunity to organize themselves to be compliant.

In particular, licensing was dependent upon a junket either being a natural person, or exclusively owned by natural persons. This was intended to facilitate transparency, and to prevent the public flotation of shares in incorporated junkets.

Licensing of junkets, which takes account of their “suitability” to conduct the business, is merely a threshold requirement for a junket to do business with a Macau gaming concessionaire. Once licensed, a junket must enter into a written contract with each concessionaire with which it plans to work. These contracts have evolved over time as the responsibilities imposed upon junkets under other legislation have increased, such as AML reporting and credit law.

Moreover, the obligations imposed on concessionaires have also increased, particularly in complying with mandated Minimum Internal Control Requirements. By licensing a junket operator, the regulator is not warranting that the operator is fit for purpose; that is a matter for each concessionaire to determine through its own inquiries. Concessionaires have a strong interest in ensuring that their contracted junket operators comply with their legal obligations for two primary reasons. First, they may be held jointly liable with the junket operator for any wrongdoing that occurs on casino premises. Secondly, all of the gaming concessionaires are publicly traded and listed corporations; there is considerable reputational, governance and legal risk involved for them in contracting junket operators. The fact that an operator is licensed does not absolve them of responsibility for oversight of their compliance with both the general law, and with the terms of their contracts.

A further factor which supported this approach is that three of the concessionaires are associated with Nevada casino licensees. Nevada Revised Statute 463 regulates gaming and industry participants in accordance with pronouncement of the State’s public policy parameters for the industry. The very first of those is the following: “The gaming industry is vitally important to the economy of the State and the general welfare of the inhabitants.” Those same words could easily have prefaced Law 16/2001.

Unlike Macau, with which it shares a strong dependence on gaming as a source of employment and government tax revenue, Nevada seeks to exert regulatory authority over its licensees and their affiliates when they involve themselves in foreign gaming operations. NRS 463.720 details a number of practices which are prohibited when a licensee (or affiliate under its control) is involved in foreign gaming operations. These include failing to conduct those operations in accordance with the standards of honesty and integrity required for gaming in Nevada, or entering into an association considered “unsuitable” for a Nevada licensee because it is contrary to the public policy of Nevada concerning gaming.

What is remarkable, given the periodic yelps of outrage concerning Macau’s regulation of junkets, is that Nevada has generally accepted that a jurisdiction can still function to a level it considers acceptable, and suitable for participation by its licensees, even if it does not as rigidly proscribe or enforce sanctions against criminal organizations or behavior. The normative standards to which some would have every jurisdiction aspire are not adopted by either of the two largest gaming jurisdictions on the planet.

That demonstrates several things. First, there is no regulatory gold standard. If there was, every jurisdiction would be doing it, or aspiring to. Secondly, neither jurisdiction has the luxury of a large, diversified economic base; pragmatism requires them to be rather more expansive and progressive in their approach to their principal industry. That doesn’t mean abandoning standards, rather working co-operatively with the regulated to progressively lift them. Macau’s most recent AML Mutual Evaluation is testament to the wisdom of this approach.

Regulation 6/2002 came into force in Macau when GGR attributable to junket business was in excess of 70% of all casino GGR. Heavy-handed regulation and a high bar for suitability could conceivably have brought down the SAR, and left China with a problem it could not easily address. In part, this explains the PRC’s continuous exhortations to the SAR to diversify its economic base … clearly easier said than done, given little obvious progress has been made in the past 10 years.

Finally, to tax considerations. Law 16/2001 introduced the concept of a withholding tax on junket commissions. Junket remuneration received by way of a share of GGR enjoys an exemption from income tax, due to the fact that gross revenue is taxed in the hands of the concessionaire deriving it. While the full 5% has never been adopted, the point of the withholding was to accustom the junket operators to the discipline of being taxed on their earnings, at the time a novel concept.

Finally, to tax considerations. Law 16/2001 introduced the concept of a withholding tax on junket commissions. Junket remuneration received by way of a share of GGR enjoys an exemption from income tax, due to the fact that gross revenue is taxed in the hands of the concessionaire deriving it. While the full 5% has never been adopted, the point of the withholding was to accustom the junket operators to the discipline of being taxed on their earnings, at the time a novel concept.

As someone involved intimately in the set up and execution of this regime, it would be tempting to go defensive. I don’t need to do more than cite history and the responses adopted to the hand dealt to Macau. The current regulatory regime has delivered results consistent with context, circumstance and the public interest of the people of both Macau and arguably the PRC, which has had none of the issues it has experienced with the Hong Kong SAR.

I reckon that makes for good law, just as there are other good gaming laws as pertain in Nevada and Singapore: they speak to their origins and respective public interests, and allow pragmatism a role.