The shenanigans over Sands China’s Cotai land rights do Macau little credit in the wider world

If we’ve learned anything at all from studying Macau government policy as it relates to the gaming industry, it’s this—when it comes to decision making, it isn’t over until it’s over. And even when you think it’s over it may not be over. At the time Inside Asian Gaming went to press, the possibility of Las Vegas Sands Corp. (LVS) getting back its ‘lost’ undeveloped land on Cotai known as Plots 7 and 8 appeared still to be alive.

An interesting question is whether Sands China wants to hold on to Cotai 7 and 8 because it desperately and urgently wants to build on them, or whether it wants to hold on to them because it doesn’t like the idea of having Stanley Ho’s casino company SJM as a neighbour. SJM has repeatedly said it covets the site and is making all the right noises to the government about focusing a Cotai project on a more general entertainment theme. That’s in line with the government’s aspirations to focus more on tourism and a little less on gambling. Anyone who looks closely at the history of SJM’s operations and that of its Ho family predecessor STDM, however, will be taking the new ‘family friendly’ incarnation of SJM with a fairly large pinch of sodium chloride. Macau is all about casinos, no matter how much lipstick local politicians like to put on the gaming pig.

Big picture

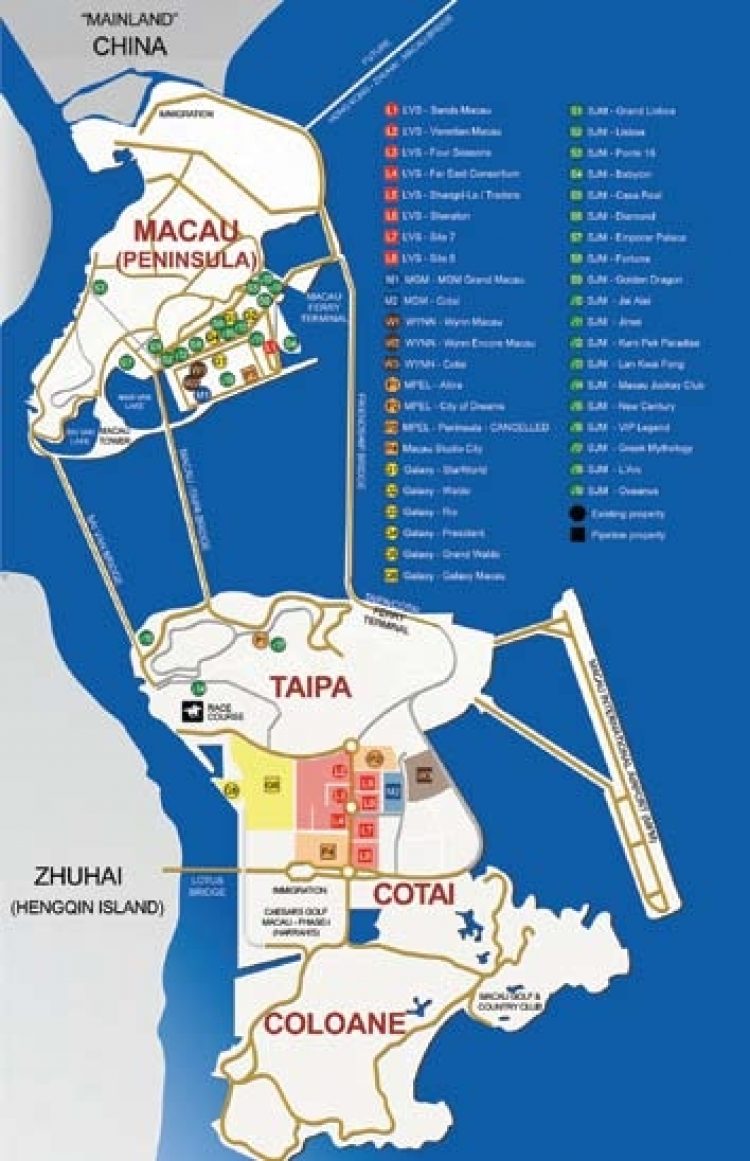

And even if SJM were allowed to build a casino with a family friendly face, it doesn’t answer the question of what exactly Cotai is supposed to be. Relatively new Macau-watchers would be forgiven for assuming Cotai was always meant to be the Las Vegas Strip plonked down in the South China Sea. That’s not the case.

Those who lived in Macau prior to the boom brought by casino liberalisation in 2002 will be aware that under a government plan drawn up in the early 1990s, Cotai was envisaged as primarily a residential area, supporting 180,000 residents and with only sufficient hotel and convention facilities to support 40,000 tourists at any one time. In 1999, that Cotai plan was amended and replaced with the casino-heavy zoning we know today. In 2002, reportedly against his initial better judgement, Sheldon Adelson, the Chairman and CEO of LVS, was persuaded to work with the government to turn what was a boggy reclamation area into a new casino zone.

In an interview with the Las Vegas Review-Journal in May 2006, when work on the US$2.4 billion Venetian Macao was already well under way, Mr Adelson described his original doubts.

“At first, I thought it was political exile,” Mr Adelson recalled. “I thought Stanley Ho had some influence that he got me off the peninsula because that’s where he believes the centre of everything is. All I was hoping was that I could get a location in which I could really do something.”

It’s possible to argue that without The Venetian Macao’s presence, Cotai could never have taken off as an alternative gaming destination to the traditional downtown casino area on Macau peninsula, and SJM wouldn’t currently be sniffing around for a home there. It’s difficult to imagine City of Dreams having the pulling power by itself to bring in hundreds of thousands of tourists from China and around the world direct to Cotai.

Now such is the draw of Cotai and such is the demand for land there that the government even allowed the selling off of a site there that had previously been reserved for an extension to Macao University of Science and Technology. That was much to the dismay of several lawmakers including Ng Kuok Cheong, who said in the Macau media in February 2007: “The purpose of use has been changed without any announcement or public consultation”.

If anything, this example goes to show the depth of incoherence that exists in Macau’s strategic land use policies. And with another 865 acres of land due to be reclaimed from the sea in the next few years, the danger is that without some fresh coherence added to the planning issue, the same kind of mistakes will be made all over again.

Added to the lack of coordination appears to be a dose of bad faith directed towards Sands China. The idea that LVS may ‘lose’ Cotai 7 and 8—two parcels of land south east of the Four Seasons—tends to assume it was LVS’s in the first place. Technically, it was not. The reason that the company had spent upwards of US$150 million on preparing the ground for development is that Sands had previously been given the impression by Macau officials that the land was its to use. Under the old easygoing Macau, legal permissions on land were generally regarded by local developers and officials alike as a slightly tiresome technical footnote designed to provide lucrative employment for local lawyers. What really mattered under the old Macau was getting political support behind the scenes. When that was in place, all things were possible.

The more things change

With political support, all things may still be possible, even in the new Macau. The problem is it’s difficult to know whether the rules of ‘new’ Macau are simply the rules of ‘old’ Macau packaged more presentably and more slickly for the benefit of the outside world. That’s because no one—apparently not even the public servants that are supposed to administer the system—really seem to know what the ‘rules’ are. Some evidence in support of this argument emerged in 2007, when the government was planning to build a new prison on Coloane, the most southerly of Macau’s original two islands. The Land, Public Works and Transport Bureau, which in theory is in charge of land management and urban planning, admitted in the weekly Catholic newspaper O Clarim that it didn’t know anything about the project. The fact that Ao Man Long, a former director of the bureau eventually ended up behind bars at the old prison for soliciting and taking massive bribes on public works projects might possibly have vindicated the government’s decision to keep the new building’s layout hush hush.

It’s not the case that Macau has no planning ‘rules’ at all. It’s quite good at setting out and enforcing the contracts with the casino operators in terms of the proportions of gaming space, hotel capacity and convention space there should be at each property. The difficulty comes with the big picture stuff. These are the decisions that have strategic consequences and perhaps major cost implications for the operators over many months or even many years.

The only person who can reasonably be assumed to have the big picture in planning for the gaming industry in Macau is the territory’s Chief Executive Chui Sai On. And he doesn’t appear overly anxious to share that information. Mr Chui’s role in Macau seems akin to Sylvester Stallone’s character in the 1995 Hollywood film Judge Dredd, about a comic book hero who enforces a semblance of order in an otherwise anarchic and post-apocalyptic world. “I am the law!” states Judge Dredd when a baddie questions his authority.

In Macau, facts related to policy on new gaming development are in relatively short supply compared to speculation on that topic. What facts do we actually know about the Cotai land allocation situation in relation to gaming and tourism projects? Here are a few key ones:

April 2009—Stanley Ho, chairman of SJM, states he is interested in buying out LVS’s interest in Cotai 5 and 6. His move comes in the wake of the global financial crisis that led in November 2008 to LVS announcing it was suspending work on 5 and 6 due to funding issues.

November 2009—LVS announces it has received a final draft land concession for Cotai 5 and 6, with an initial land premium of MOP700 million (US$87.5 million) and a total land premium ultimately of MOP1.9 billion. The US$4.1 billion project will have 300,000 square feet of gaming space and 6,400 hotel rooms under the Sheraton, Traders, Shangri-La and St Regis brands.

November 2009—LVS raises US$2.5 billion by floating its local unit Sands China on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange.

November 2009— LVS says it has been given an extension on the August 2011 deadline originally agreed with the government for the construction of Cotai 3—known as the Far East Consortium site, next door to the Four Seasons. The site, originally slated to have a Holiday Inn, an InterContinental Hotel and an Emperor Hotel, is given a new completion deadline of April 2013.

December 2009—LVS announces it has secured in principle US$1.75 billion debt funding towards the US$4.1 billion cost of Cotai 5 and 6 and that it will recommence construction at the earliest available opportunity.

March 2010—the Macau government says it will impose a 5,500 cap on the number of live gaming tables in the market henceforward until the end of 2013. That reduces by roughly one-third the number of live tables permitted for Galaxy Macau, Galaxy Entertainment Group’s new Cotai project, and Sands China’s Cotai 5 and 6 in their first phase openings.

April 2010—LVS says in its first quarter results filing to the SEC that it could lose its entitlement to Cotai Plot 3, and with it US$35.6 million in capitalised costs, if it is not able to develop the site.

April 2010—the Macau government announces a ‘one-for-one’ policy on construction labour recruitment (i.e. one local hired for every imported worker). This effectively stops dead LVS’s plans to ramp up building work on Cotai 5 and 6.

May 2010—The developers of the stalled Macao Studio City project on Cotai are sent a letter from the Macau government stating it is considering taking back the 32.3-acre site unless there is some evidence that the project (currently mired in litigation between two of the partners) will go ahead.

June 2010—Wynn Resorts announces plans to build a new resort on Cotai with a hoped for completion date in 2014. The land had previously been allocated to Wynn on terms similar to LVS’s neighbouring land concession; i.e., in principle but subject to final legal permission.

June 2010—Ambrose So, Executive Director and CEO of SJM Holdings, calls on the government to re-tender the rights to Cotai 7 and 8.

July 2010—Sheldon Adelson says a fourth quarter 2011 completion date for Cotai 5 and 6 is possible.

August 2010—Michael Leven, acting CEO of Sands China, says the company has spent US$162 million on preparatory work for Cotai 7 and 8 and says, in response to SJM’s stated interest in the land that it will “certainly defend positions on sites 7 and 8”.

August 2010—Francis Lui, Deputy Chairman of Galaxy Entertainment Group, tells journalists the labour squeeze has “slightly affected” the timetable for opening Galaxy Macau, the company’s US$1.8 billion Cotai project. Privately analysts are briefed to expect a second quarter 2011 opening, not the first quarter launch originally planned.

September 2010—Ambrose So reiterates to Inside Asian Gaming that SJM would be interested in developing a project “possibly with an emphasis on recreation facilities” on the site of Cotai 7 and 8.

September 2010—SJM sends a letter to the Macau government asking to take over Cotai 7 and 8.

October 2010—Steve Jacobs, sacked in July as CEO of Sands China, files a lawsuit against LVS in a Nevada court alleging breach of contract. The deposition claims Mr Jacobs was asked to organize “secret investigations” on Macau government officials so that any negative information could be used against them.

November 2010—LVS says a completion date on Cotai 5 and 6 “is not determinable with certainty” until adequate labour quota is received for construction work.

November 2010—A company controlled by Angela Leong, fourth consort of Stanley Ho, announces plans to build a US$1.3 billion ‘theme park’ on two million sq. ft of land next to the Macao Dome, an indoor sports facility built for the East Asian Games in 2005.

2nd December 2010—The government sends a letter to Sands China, LVS’s Hong Kong-listed unit, saying its application for a land concession to develop the 1.1 million sq. ft Cotai land parcel referred to as Cotai 7 and 8, “has not been approved”.

2nd December 2010—LVS issues a filing to the US Securities & Exchange Commission giving notice of the decision.

2nd December 2010—LVS’s share price falls 4.2% to US$49.17 in 4pm trading on the New York Stock Exchange after hitting a low of US$47.20 earlier in the day.

3rd December 2010—LVS asks Macau’s Chief Executive to review the decision on Cotai 7 and 8.

3rd December 2010—SJM again reiterates its interest in Cotai 7 and 8 – just in case anyone has forgotten.

5th December 2010—Jaime Carion, Director of Macau’s Lands, Public Works and Transport Bureau, when buttonholed at the weekend by a journalist on the sidelines of a public event, says the government is now looking at developing non-gaming projects on Cotai. “We are looking at more diversification in the Cotai area rather than being exclusively for the casino industry. We want to promote more cultural activities, sightseeing and recreation for families,” he states.

Just as interestingly, Mr Carion also said the Sands China application procedure for Plots 7 and 8 was not fully complete and the government would announce the result “at the most convenient time”.

“Everything relating to land management will be done accordingly with the Land Law and its additional legislation. But the procedures are still ongoing and there is no final decision yet. The government will announce the decision in the most convenient time,” said Mr Carion.

That phrase “not fully complete” suggests the door may still be open to LVS. As has been proven previously in Macau, though, such signals can mean everything or they can mean absolutely nothing.

Given this opacity and the shortage of hard facts, it’s hardly surprising that analysts and commentators are forced to resort to speculation regarding the future development of Macau’s gaming sector. During the height of the Cold War between the Soviet Union and the US, when the West sought to understand what was going on inside the Soviet leadership, such inspired guesswork was known as ‘Kremlinology’.

Inside Asian Gaming doesn’t claim to have an inside track on Macau government thinking, but it has spoken to people familiar with the Cotai legal process. They suggest there is a real possibility that LVS may still get its hands on 7 and 8. That’s not because LVS has strong grounds for an appeal against the process (it apparently doesn’t). It’s because the government would probably prefer not to have to pay LVS compensation for the work it has already done on the site and because any such compensation claim could mire Cotai 7 and 8 in litigation that could effectively tie up the land and prevent it being used by anyone for years to come.

“For the last two or three years the government has asked Sands China to do consolidation work on lots 7 and 8. LVS has spent somewhere between US$100 million and US$150 million,” a source told IAG.

“The company could sue the government to reclaim that money, and I don’t think the government wants that. If that aspect of the matter goes to court, then the litigation could be endless. You could get a situation where no one will ever build anything on Cotai 7 and 8,” added the source.

Dirty linen

There are other consequences that could come from a court battle between LVS and the government over Cotai 7 and 8. All kinds of unpleasantness relating to the government’s relationship with the casino operators—the sort of cringe-making moments experienced during Hong Kong businessman Richard Suen’s lawsuit against LVS in Nevada—could become available to the media under the cloak of legally privileged court reporting. To use the language of the Cold War, that could risk what military analysts of the nuclear missile standoff between the US and the Soviet Union used to refer to as ‘mutually assured destruction’ or ‘MAD’ for short.

Thus far, LVS is taking a subtler, and it hopes a more effective approach, based on administrative law.

“LVS didn’t appeal against the decision stated in the government’s letter,” the contact told IAG.

“A formal appeal means a court hearing. At that administrative level it’s only possible to appeal when there’s someone higher in authority to appeal to. This decision “to not approve” was made by the Chief Executive, so in terms of administrative law there’s no one beyond him. What LVS has done instead is to ask the government to re-evaluate and reconsider the position stated in the letter.

“Technically, the government has 15 days from the date of LVS’s request for re-evaluation to give the company an answer. In reality, it might take longer. But if it’s kept at that administrative level, the decision could take less than two months.

“It’s still possible the government will reconsider and grant [Sands China] the land.”