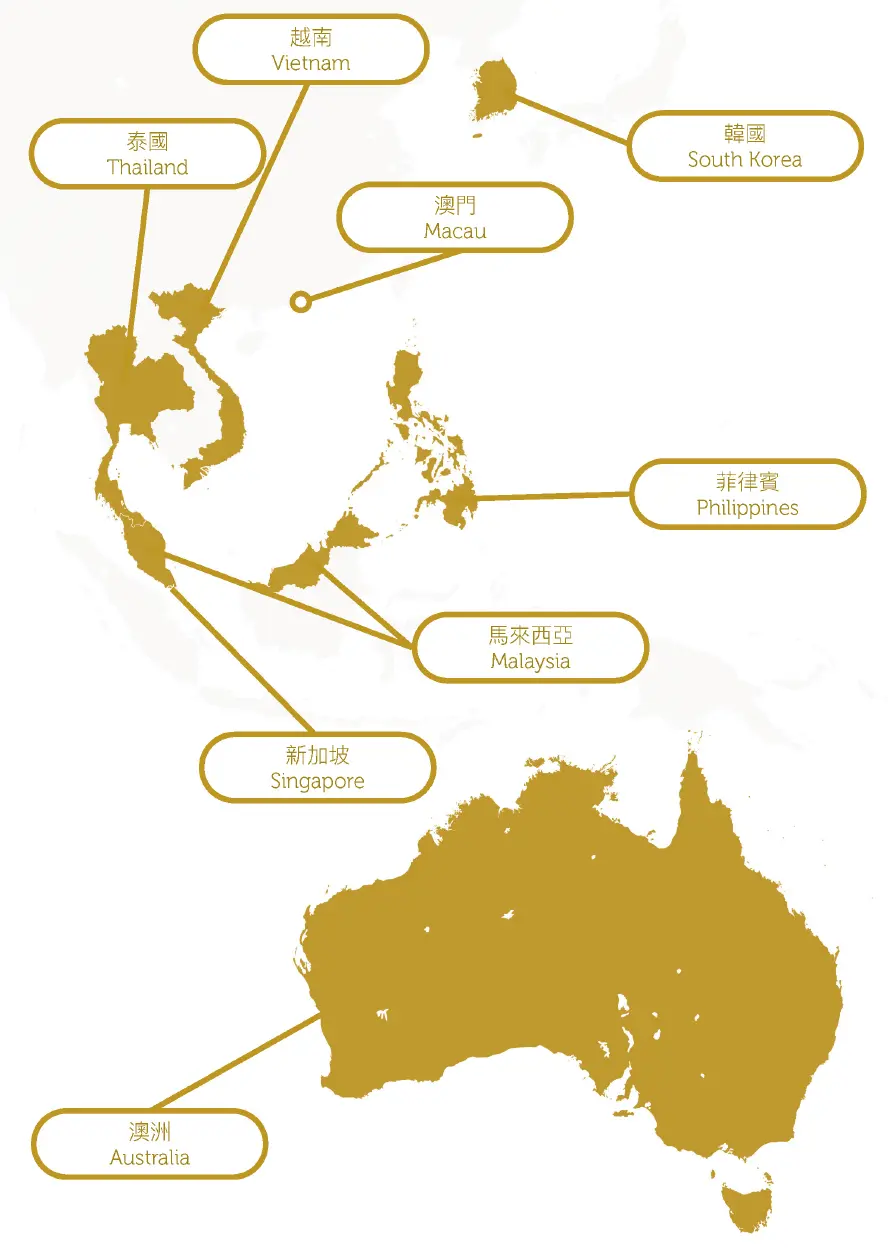

Inside Asian Gaming takes a deep dive into the state of Asia-Pacific’s key gaming markets: who’s hot, who’s not and where will the surprises come from in the near-term?

The pandemic years are now a distant memory, and the Asia-Pacific gaming industry has settled into what might best be described as its new-norm. For some, that’s great news. Macau, for example, has printed its three best post-COVID months in May, June and July, suggesting the market has finally grown accustomed to the reality of a world without junkets (or very few at least). Singapore is also on a heater, with Marina Bay Sands continuing to astound on the sheer power of its numbers, and local rival Resorts World Sentosa spending big in the belief it can do the same.

But it’s not all rosy. Even as its domestic iGaming sector booms, the Philippines is seeing a major decline in its land-based gaming segment – impacted by a decline in VIP and fewer international arrivals from South Korea and China. As for Australia, the jury is out on whether there will be a legal casino industry at all in the long-term, given the ongoing fallout of inquiries into former industry titans Crown and Star. We go around the grounds to take a closer look at how the eight major Asia-Pacific jurisdictions are tracking.

But it’s not all rosy. Even as its domestic iGaming sector booms, the Philippines is seeing a major decline in its land-based gaming segment – impacted by a decline in VIP and fewer international arrivals from South Korea and China. As for Australia, the jury is out on whether there will be a legal casino industry at all in the long-term, given the ongoing fallout of inquiries into former industry titans Crown and Star. We go around the grounds to take a closer look at how the eight major Asia-Pacific jurisdictions are tracking.

Macau

Macau

Macau has proved a challenging market to read since COVID. After roaring back to life in the months following January 2023 when authorities suddenly opened the border, momentum slowed in the back half of 2024 due to concerns around China’s economy, a crackdown on illegal money exchange activities (which had aided customer liquidity) and a lag in recovery of the base mass market, all of which capped gaming revenues at a little under MOP$20 billion (US$2.47 billion) per month.

But the sands appear to be shifting again in recent times, with GGR breaking through that MOP$20 billion barrier in May – notching the best monthly result in almost five-and-a-half years in the process at MOP$21.19 billion (US$2.62 billion) – and maintaining that momentum in June at MOP$21.06 billion (US$2.60 billion). July then proceeded to set yet another post-COVID record – defying all forecasts – at MOP$22.13 billion (US$2.73 billion).

While analysts noted that the June result was aided by higher VIP hold, there have been other important factors at play at the upper echelons. Investment bank JP Morgan pointed to the return of high-profile performers to Macau as having attracted a significant number of premium players, while general sentiment among that segment is thought to have improved due to positive wealth effects from stock markets and the continued ramp-up of Capella Macau – the uber-luxury all-suite tower at Galaxy Macau that soft-opened in late April.

While analysts noted that the June result was aided by higher VIP hold, there have been other important factors at play at the upper echelons. Investment bank JP Morgan pointed to the return of high-profile performers to Macau as having attracted a significant number of premium players, while general sentiment among that segment is thought to have improved due to positive wealth effects from stock markets and the continued ramp-up of Capella Macau – the uber-luxury all-suite tower at Galaxy Macau that soft-opened in late April.

Citigroup noted in a July note that Galaxy in particular was reaping the benefits via the presence of many more big-spending “whales” than at the same time last year. Although these whales were observed Macau-wide, a healthy proportion had made their way to Galaxy Macau’s premium gaming rooms.

Macau gaming stocks have not yet responded to this improved sentiment, but the trend is clear, with multiple banks and research houses having recently upgraded their Macau forecasts.

Year-on-year GGR growth, which sat at less than 1% through the first four months of 2025 combined, jumped to 1.7% through May and to 4.4% through June – highlighting the sheer strength of the end-of-quarter. Seaport Research Partners now estimates FY25 growth to be around 7%, aided by a 9% year-on-year increase in H2.

The key questions facing Macau now, other than the snail’s-pace return of the base mass segment, largely revolve around the demise of the satellite casino industry. In early June, the government revealed that all 11 existing satellite casinos would close by year’s end, albeit with SJM flagging its intention to acquire Ponte 16 and L’Arc and bring them in as self-owned casinos.

The key questions facing Macau now, other than the snail’s-pace return of the base mass segment, largely revolve around the demise of the satellite casino industry. In early June, the government revealed that all 11 existing satellite casinos would close by year’s end, albeit with SJM flagging its intention to acquire Ponte 16 and L’Arc and bring them in as self-owned casinos.

Although the satellites currently contribute only around 5% of Macau’s total GGR, any failure by the city’s integrated resorts to absorb those customers who have traditionally preferred the more intimate surrounds of their favorite satellite would represent an unwelcome hit to earnings.

SJM remains the one to watch here: will it lose market share, or could the relocation of a few hundred tables to its Cotai and peninsula IRs generate higher returns than previously?

Philippines

Philippines

For a while at least, the Philippines was the golden child of the post-pandemic world. Land-based licensed casino revenues surged in 2023 to Php207.5 billion (US$3.65 billion), an all-time-high buoyed by the rapid return of international travel and renewed strength in its premium gaming segments.

But the sector has been challenged in recent times, with licensed casino GGR dropping back to Php201.8 billion (US$3.53 billion) last year – including a 5.3% decline at Manila’s Entertainment City IRs – and continuing that trend with significantly large declines through the first half of 2025.

There appear to be two key reasons for this, keeping in mind that domestic gaming machine revenues have at least managed to hold their own. One, the ban on the Philippine Offshore Gaming Operators (POGO) industry that took effect from 1 January 2025 has hurt the local VIP gaming scene, because individuals linked to POGOs comprised a sizeable chunk of the premium player base. And two, visitation from South Korea and China, once the Philippines’ two largest tourism source markets (South Korea still ranks No.1), is way down in 2025, possibly reflecting safety fears given the negative publicity that surrounded POGOs during their recent demise.

Only time will tell if PIGO – the unofficial term for the Philippines’ rapidly growing domestic online gaming, or eGames, sector – goes the same way as POGO. eGames has been the fastest growing sector across the country in recent quarters and in Q1 became for the first time the local gaming industry’s top revenue driver, with GGR of Php51.39 billion (US$904 million) representing 49.4% of total first quarter GGR according to PAGCOR. More recently PAGCOR revealed that eGames GGR topped US$2 billion for the first six months of 2025 combined.

However, a push by some senators to impose tighter regulatory restrictions upon the industry has sparked widespread debate on whether online gaming should be banned in the Philippines altogether.

However, a push by some senators to impose tighter regulatory restrictions upon the industry has sparked widespread debate on whether online gaming should be banned in the Philippines altogether.

Industry representatives have warned against such a move, noting that a total ban would simply shift online gambling activity to unregulated offshore sites, but it remains to be seen whether cool heads prevail.

On a positive note, there continues to be a healthy dose of new supply in the market, with the Westside City development to take the number of genuine IRs in Manila to five when it opens in 2026. There are also comprehensive expansion projects underway at New Coast Manila and further north at Clark’s Hann Casino Resort. Likewise, Newport World Resorts operator Travellers International Hotel Group is set to open new casino projects within townships in Cebu and Boracay developed by affiliate Megaworld Corp. This, along with the ongoing refurbishment of PAGCOR’s self-owned casinos ahead of privatization, means industry suppliers still see the Philippines as the place to be.

On a positive note, there continues to be a healthy dose of new supply in the market, with the Westside City development to take the number of genuine IRs in Manila to five when it opens in 2026. There are also comprehensive expansion projects underway at New Coast Manila and further north at Clark’s Hann Casino Resort. Likewise, Newport World Resorts operator Travellers International Hotel Group is set to open new casino projects within townships in Cebu and Boracay developed by affiliate Megaworld Corp. This, along with the ongoing refurbishment of PAGCOR’s self-owned casinos ahead of privatization, means industry suppliers still see the Philippines as the place to be.

Singapore

Singapore

Now firmly established as Asia’s capital of high-end tourism, Singapore appears to be the epitome of the old adage “build it and they will come”. After all, why else would duopoly operators Las Vegas Sands (LVS) and Genting Singapore agree to spend a combined US$13 billion to upgrade and expand their already highly lucrative integrated resorts?

The proof is very much in the pudding. Marina Bay Sands, long touted as the most profitable casino in the world with EBITDA margins sitting above 50%, recently completed a US$1.75 billion transformation of its existing hotel room inventory that included growing the number of suites on offer from 180 to 775.

In the very first quarter in which the property was able to enjoy the benefits of this additional suite product, MBS reported an all-time record quarter, with revenue up 36.6% year-on-year to US$1.39 billion and Property Adjusted EBITDA up 36.9% to US$768 million at an astonishing 55.3% margin. That places annualized EBITDA run-rate at higher than US$3 billion, albeit aided by strong VIP hold for the quarter.

So, is it any wonder LVS is investing another US$8 billion to expand the property?

The ground breaking ceremony for this expansion, which will see a fourth hotel tower built, took place in mid-June and when complete will add another 570 suites plus signature rooftop and dining experiences, luxury retail boutiques, more gaming, holistic spa and wellness amenities and around 200,000 square feet of premium meeting space, while a purpose-built 15,000-seat arena will look to enhance the live entertainment scene in Asia.

Genting Singapore’s Resorts World Sentosa, located about 10 minutes from MBS on Sentosa Island, is in the midst of its own US$5 billion upgrade and expansion project, and analysts are growing increasingly confident it will achieve similarly positive results.

“We think the strong high-end consumption at MBS bodes well for Genting Singapore’s own capex decision to upgrade hotel rooms to more premium offerings,” Nomura analysts wrote in a recent note. “With the Luxury Collection (high-end hotel product) slated to open to the public at end-October, we see growth in 2H25 earnings for Genting Singapore.

“Performance is likely to improve also, in our view, as the refurbished Forum – now rebranded WEAVE – is also seeing tenants move in from July onwards and should meaningfully contribute to earnings growth in 2H25/2026.”

Although ongoing upgrade works saw 1H25 results at RWS come in way below its cross-town rival, the expanded property looms as an exciting prospect. It recently saw the new Singapore Oceanarium – three times larger than the former S.E.A. Aquarium – open to the public, while other new offerings are to include a waterfront development comprising an 88-meter tall “light sculpture”, an “immersive, experiential mountain trail”, a four-story world-class retail and dining podium with entertainment offerings, and two new luxury hotels featuring 700 keys.

The evolution of Singapore into a world-class gaming and entertainment destination continues unabated.

Australia

Australia

Australia was once the golden child of the Asia-Pacific casino industry. An early mover with the opening of Hobart’s Wrest Point in 1973 and one of the region’s first true integrated resorts in Crown Melbourne in 1994, it rings true to this day that many of the senior casino executives found across Asia began their career journeys on Aussie shores.

But the great Australian casino dream has since collapsed – and spectacularly so – following a raft of inquiries into the sector that began in 2020 prompted by a series of damning media reports alleging criminal activity on Australia’s casino floors linked to Macau-based junkets.

Those inquiries, specifically the Bergin (NSW) and Finkelstein (Victoria) examinations of Crown Resorts, as well as the NSW Bell Inquiry into Star Entertainment Group, ultimately saw the casino licenses of the country’s two dominant operators suspended pending the fulfilment of expansive transformation requirements. Some have argued the two got off lightly by not losing their licenses altogether, although remediation has proven to include complex and sweeping overhauls of their AML and responsible gaming systems. As Star’s repeated failures have shown, implementing such drastic change is easier said than done. Despite overhauling its entire executive team – twice – Star has still not returned to suitability and, faced with rising regulatory costs and the annihilation of its customer base, has lost so much money in the past few years that its survival is now reliant on an AU$300 million (US$195 million) rescue package from US casino operator Bally’s Corp, in partnership with major shareholder Bruce Mathieson. The next 12 months will determine whether Star and its casinos in Sydney, the Gold Coast and Brisbane survive.

Crown, which was bought out by US private equity giant Blackstone in 2022, has fared better than Star. For one, it took its remediation process seriously from day one, bringing in a team led by former Macau casino executive Ciarán Carruthers to do what it takes to return to suitability.

Backed by Blackstone’s considerable financial reserves, Crown ultimately succeeded in that mission – winning back its Melbourne and Sydney licenses in 2024 and just a few months ago getting the green light at Crown Perth as well.

Yet the outlook for all Australian casinos remains choppy, particularly with AML watchdog AUSTRAC having recently flagged regional properties The Ville in Townsville and Mindil Beach in Darwin as having piqued its interest.

The reformation process that Crown went through – and that Star is still in the process of implementing – has required hundreds of millions of dollars of investment that has significantly cut into the bottom line. At the same time, the collapse of the Macau junket industry, coupled with heavy restrictions now governing the transfer of cash to Australian casinos from international players, has killed the VIP segment. Domestically, the introduction of mandatory carded play and the complicated sign-up processes linked to it have driven local players away from casino floors and back to pubs and clubs, which at present are not required to put their customers through the same due diligence.

Essentially, the Australian casino industry is at a tipping point. The sobering reality is that their customer base has shifted – perhaps forever – and at a time when the regulatory playbook has moved from one extreme to the other.

This struggle is no longer about profitability; it’s a fight for survival. And while the onus has rightly been put on the operators to mend their wicked ways, it might also be time for regulators to strike a better balance in how they govern the industry. As operators fight to stay afloat, the question must be asked of government: are you prepared for the consequences if they can’t?

Malaysia

Malaysia

Malaysia is unique in our roundup of Asian markets in that it is home to just one integrated casino resort – the legendary Resorts World Genting (RWG) in the Genting Highlands outside of Kuala Lumpur.

RWG was the brainchild of Lim Goh Tong – the father of current Genting Group Chairman and CEO Lim Kok Thay – who in the late 1960s responded to the government’s desire to boost economic diversification and drive tourism by proposing a mountain resort. He argued, however, that a casino was needed to justify the cost of development and in 1969 was granted a single casino license as a special exception rather than as part of broader gambling legalization.

This was the start of the Genting empire, and to this day it remains the company’s flagship property and one of its main economic engines.

RWG’s post-COVID recovery has been choppy, although it did report a 6% year-on-year increase in revenues to MYR6.82 billion (US$1.61 billion) in 2024, with Adjusted EBITDA of MYR2.09 billion (US$492 million).

While the property should benefit from a sharp increase in international visitor arrivals to Malaysia and nationwide tourism receipts during the first half of 2025, this hasn’t yet been realized, with the company reporting a slight improvement in its mass gaming segments but an 18% decline in VIP volumes.

The minor growth in mass has also not been enough for RWG to reopen the two mass gaming floors – Circus Palace Casino and Hollywood Casino – it closed for renovations in February 2024. Hollywood Casino partially reopened late last year, albeit at around one-third capacity, while Circus Palace remains closed. Analysts have cited the full reopening of both as key to their raising earnings estimates, but operator Genting Malaysia has stated it will only do so as demand dictates.

Of greater concern in the long-term is an increase in service tax charged by the government from 6% to 8% as of March 2024, which has further eaten into margins.

On a positive note, the 20% increase in international visitation to Malaysia between January and May included a 38.8% rise in arrivals from China, suggesting better days ahead for the country’s monopoly casino operator.

On a positive note, the 20% increase in international visitation to Malaysia between January and May included a 38.8% rise in arrivals from China, suggesting better days ahead for the country’s monopoly casino operator.

South Korea

South Korea

South Korea’s mostly foreigner-only casino market was hit particularly hard during the pandemic years, given its heavy reliance on international visitation, but at least some of the country’s leading operators have enjoyed a surprisingly strong renaissance since.

The Korea Economic Daily reported in July that the nation’s three leading foreigner-only casino operators – Paradise Co, Grand Korea Leisure (GKL) and Lotte Tour, all listed on the Korea Exchange – reported combined drop amount of KRW3.42 trillion (US$2.46 billion) in 2Q25, up 11.9% year-on-year and 13.8% quarter-on-quarter to a new all-time record. This also took 1H25 drop to a record KRW6.42 trillion (US$4.62 billion), up from KRW6.09 trillion (US$4.38 billion) a year earlier.

Paradise, which operates casinos in Seoul, Busan and Jeju and holds a 55% stake in Incheon’s first integrated resort, Paradise City, has stood out with 1Q25 casino sales reaching KRW115.6 billion (US$81.5 million) at its three wholly-owned casinos and KRW139.1 billion (US$98.1 million) at Paradise City, up 7.3% year-on-year. The June quarter saw those figures bettered again as Paradise set a new all-time quarterly record for casino revenue.

Paradise appears confident in the momentum it has generated, committing last year to developing a new 200-suite hotel in Seoul – scheduled to open in 2028 – offering premium services for foreign VIPs, luxurious Korean-style cuisine and wellness amenities. Complementing new VIP space at its Seoul casino Paradise Walkerhill, the hotel is said to form part of Paradise’s revamped strategy to attract more international high rollers to its properties.

In Jeju, the return of Chinese visitation following the recent easing of visa restrictions has helped Lotte Tour finally gain traction at its Jeju Dream Tower integrated resort. Opened in late 2020, right into the teeth of the pandemic, Jeju Dream Tower has been on a roll in 2025, setting a series of new drop and revenue records for the property including an all-time-high drop amount of KRW274.2 billion (US$198 million) in July. Combined Q2 drop of KRW668.5 billion (US$48.1 million) was up 63% from the same period in 2024.

Korea’s outlier is, of course, Kangwon Land – the only casino in the country at which locals are permitted to gamble. Overseen by the National Ministry of Knowledge Economy and 51% government-owned, Kangwon Land has traditionally generated roughly the same amount of revenue as Korea’s 17 foreigner-only casinos combined – although government-imposed restrictions on tables and betting limits have in recent years kept the casino’s performance subdued (by its lofty standards).

However, the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism recently permitted limits to be raised significantly on two VIP tables and four mass tables at Kangwon Land, which subsequently reported a 9.2% increase in GGR in Q2 to KRW361.5 billion (US$260 million).

Like Paradise, Kangwon Land has recognized the need to enhance its offering to broaden its appeal and will spend US$128 million to develop a second casino facility – part of a much larger US$1.9 billion upgrade to the facility which also includes a ski resort, golf course, theme park and other outdoor adventure attractions.

The big unknown in Korea right now is INSPIRE – the US$1.6 billion casino resort developed by US tribal casino operator Mohegan. Not entirely against expectations given questions over the size of that investment for such a niche market, INSPIRE – which opened its casino in early 2024 – has been slow to ramp. Too slow, it seems, for the property’s main lender, Bain Capital, which in February seized operational control of INSPIRE citing Mohegan’s failure to achieve agreed financial targets under its debt covenant.

Bain Capital has since confirmed its intention to sell the integrated resort, but there has been no clarity on its financial performance in the months since.

The INSPIRE situation highlights the fact that South Korea remains a risk proposition for investors, given the absence of locals gaming and exposure to unforeseen headwinds like the pandemic or regional tensions. Get it right, however, and there is money to be made.

Vietnam

Vietnam

Like South Korea, the rise of Vietnam’s casino industry has been constrained by its foreigner-only policy. Despite the impediment, three sets of investors – likely wooed by the dream that locals gaming will one day be permitted – have taken on the challenge of developing a large scale integrated resort with a mandated minimum investment level of US$2 billion: The Grand Ho Tram, located about two hours by car from Ho Chi Minh City on the east coast; Hoiana, just outside the ancient town of Hoi An; and Corona Resort & Casino, on the popular holiday island of Phu Quoc. Needless to say, operations have been challenging.

The Grand Ho Tram, which first opened in 2013 with an initial investment cost of US$500 million, is planned to eventually become a US$4.2 billion integrated resort once fully complete, offering a casino, 9,000 hotel rooms, an 18-hole golf course, villas and expansive retail options. The casino, golf course and some hotel rooms have been operational since opening.

US hedge fund giant Harbinger Capital – which covered the resort’s initial US$500 million investment – sold off its majority interest in The Grand Ho Tram’s parent company, Asian Coast Development Ltd (ACDL), to Warburg Pincus in July 2019.

Warburg Pincus subsequently inserted a new management team in early 2020, with Walt Power – a Macau industry veteran whose previous roles include SVP of Operations for Sands China subsidiary Venetian Macau Limited – named CEO.

Power has since implemented a strategy of using high-profile events, including professional boxing, mixed martial arts, casino-related VIP dinners, fashion shows and beauty pageants, to lure patrons from Ho Chi Minh City – particularly expats with access to the gaming floor. Still, the impressive property will never truly fulfil its potential until locals are granted access – a prospect that, according to industry chatter, could come sooner rather than later.

Hoiana, opened in mid-2020 into the teeth of the COVID-19 pandemic, was originally a three-way partnership between Suncity Group, Hong Kong-based investment firm VMS Group and local investment management and real estate firm VinaCapital. Utilizing the substantial database of Suncity’s associated junket business, Hoiana was envisioned as a high-end destination for VIPs before that business model hit a major hurdle with the arrest of Suncity’s chairman Alvin Chau in 2021. Part of a broader crackdown by Beijing, Chau’s arrest and eventual imprisonment ultimately led to the collapse of the Macau junket industry, with the Suncity junket business officially closing its doors in December 2021.

The listed entity of Suncity Group, which rebranded to LET Group in the wake of Chau’s arrest, has recently exited Hoiana, with VMS Group – linked to Hong Kong jewelry giant Chow Tai Fook – claiming 75% control of the property.

Long-term, Hoiana is planned to include seven development phases at a total cost of US$4 billion, with the final vision to include a multitude of hotels and residences, two 18-hole golf courses, MICE facilities, commercial space and high-end and outdoor retail alongside the existing casino, which offers around 140 gaming tables and 350 electronic gaming machines.

Locals gaming does not appear to be on the radar, but perhaps Chow Tai Fook can overcome that hurdle given its own substantial database of the rich and famous across much of Asia.

As for Corona Resort & Casino in Phu Quoc, it was the one and only recipient of a temporary license to accept locals as part of a three-year pilot program launched by the Vietnamese government in 2019. The pilot was, of course, interrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic and never really got going to any great extent again before being put on ice at the start of this year.

As for Corona Resort & Casino in Phu Quoc, it was the one and only recipient of a temporary license to accept locals as part of a three-year pilot program launched by the Vietnamese government in 2019. The pilot was, of course, interrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic and never really got going to any great extent again before being put on ice at the start of this year.

Questions could also be asked as to whether a trial of locals gaming at a destination made specifically to appeal to holidaymakers was ever going to produce effective results: data released by authorities in Kien Giang Province in 2022 showed that locals contributed just 5% of Corona’s total revenues of VND2.7 trillion (US$113 million) during the first three years of the pilot – even at a time when international travel was on ice.

Despite this, recent news reports suggest the Vietnamese government is considering allowing locals access to Corona on a permanent basis – and possibly elsewhere too – including a recommendation to scrap the program’s minimum wealth requirement in favor of a casino entry levy model similar to that utilized in Singapore.

It has also been revealed that Vietnam has approved a fourth US$2 billion IR development in Van Don, covering some 244 hectares and to be built over three phases. The development was recently awarded to local real estate giant Sun Group and will allow locals gaming, according to reports, suggesting better days may be on their way for the IRs of Vietnam.

Thailand

Thailand

Thailand has long been described as one of Asia’s great untapped greenfield gaming opportunities, but efforts to establish a regulated industry have always fallen short – largely due to the country’s renowned political instability. Sadly, that instability looks to have again scuppered legalization at a time when it finally looked like a breakthrough was imminent.

Rewind one year and the widely held sentiment was that a legal land-based casino industry had under Prime Minister Paetongtarn Shinawatra managed to garner bipartisan support. Two separate studies undertaken by the House of Representatives recommended the legalization of casino gaming within large-scale integrated resorts – or entertainment complexes as they have been dubbed in Thailand – to be located in up to five designated zones across the country. Bangkok, Chonburi, Chiang Mai and Phuket were named as leading contenders.

Such was the seeming goodwill, international operators who have been keeping an eye on Thailand – the likes of Galaxy Entertainment Group, Melco Resorts, MGM and Wynn – began increasing their local presence in preparation for the finalization of the government’s Entertainment Complex Bill and the inevitable RFP process that would follow.

But cracks began to appear in February when the Council of State decided the bill should include a stipulation that locals should only be able to enter Thai casinos if they held THB50 million (US$1.5 million) in bank deposits for at least six months. In effect, this would make Thai casinos foreigner-only, given that less than 10,000 people or 0.015% of the population fulfil this requirement, according to Bank of Thailand data.

But cracks began to appear in February when the Council of State decided the bill should include a stipulation that locals should only be able to enter Thai casinos if they held THB50 million (US$1.5 million) in bank deposits for at least six months. In effect, this would make Thai casinos foreigner-only, given that less than 10,000 people or 0.015% of the population fulfil this requirement, according to Bank of Thailand data.

There also emerged, much like in Japan a few years earlier, more vocal opposition to the government’s casino plan led by the opposition People’s Party and some noted anti-gambling campaigners.

Inside Asian Gaming looked to address many of the key discussion points via the Thai Entertainment Complex Roundtable (TECR) held in Bangkok in early June, bringing together operators, opposing voices and those positioned somewhere in between for respectful and meaningful discussion. The idea of TECR was to provide doubters with real-world examples of how international operators institute best practice in regard to responsible gambling, anti-money laundering and socio-economic contributions – and to an extent it was a success in providing deep insight into the industry for those in the room who were not fully aware of exactly what an integrated casino resort is. IAG noted, however, that two of those notable anti-gambling campaigners pulled out at the last minute, perhaps unwilling to have their reasoning analyzed by a room of experts.

Despite this, the issue of casino legalization took a huge hit in late June when – concerned over the Prime Minister’s handling of a border dispute with Cambodia – the government’s coalition partner Bhumjaithai broke away, reducing the government’s majority to just a handful and heaping further political pressure on the under-fire PM.

In a bid to buy more time, the government soon opted to remove the Entertainment Complex Bill from a planned discussion by the House in early July, effectively rendering the issue dead and buried for the foreseeable future.

One can’t help but look back to comments made by Seaport Research Partners analyst Vitaly Umansky at G2E Asia in June 2024 to realize that such an outcome was really not so surprising.

“The biggest problem is going to be on the regulatory front, and even more importantly it’s going to be on the political risk front, because to go to a public company, an international casino operator and developer, and ask them to invest US$4 billion or US$5 billion in a country that is politically at risk of having bad things happen – government changes, political unrest – I think it’s a very big ask,” Umansky said at the time.

“What is the political risk situation in a country like Thailand, where cannabis is legalized one year and has now been criminalized the next?

“The government flips, things change. That is not a stable political environment where an operator will be willing to commit billions of dollars of investment.

“If the government was to change its views and say ‘Look, we understand this is difficult’, then they can start small and build a Sands Macao, see how it goes, start utilizing those cash flows to reinvest, then start to build a proper market over time.

“But to just mandate multi-billion-dollar developments without a regulatory framework that we know can work, I think that will be a near impossibility.”