The ‘back story’ to Macau’s VIP gaming numbers

The maxim “There are three types of lies—lies, damned lies, and statistics,” has, probably appropriately, been attributed to at least three famous men of politics and letters: Benjamin Disraeli, Alfred Marshall and Mark Twain.

The phrase never seemed more appropriate than when applied to Macau gaming numbers. An operator can move up a place or two in the revenue league table but it may not help very much if the price is deterioration in higher margin mass-market business, or if the improvement was a result of a short upward blip in his VIP hold percentage, which subsequently normalises.

|

| Sheldon Adelson of LVS—a few home truths about market share |

As Sheldon Adelson pointed out in his third quarter earnings call last year, SJM’s share of Macau revenue looks unassailable at first glance (32.2% in January this year)—but not so rosy when one digs into the statistics. Most ‘SJM’ properties (16 out of the 20) are satellite casinos operating under the SJM licence but with varying degrees of autonomy in their management. That means SJM gets to keep a smaller proportion of the gross wagered in Macau than its market coverage and table numbers would suggest. Satellites are paying SJM anywhere from 20% of the gross (the traditional 40:40:20 model, whereby 40% goes to the government in tax, 40% to the satellite owner and the residue to SJM), to as little as 3-5% to SJM on a profit share basis. And market-wide, Inside Asian Gaming understands the trend is for a movement away from the 40:40:20 model. Even that bald statistic is somewhat misleading however, given that in return for giving up 15-17% of the gross, SJM is relieved of the headache of staffing those satellites. That’s no mean concession in a market short of reliable and cheap labour, and could have the effect actually of boosting SJM’s profit margin in some or all of those properties.

Minefield

The above illustration is a good indication of the minefield into which any commentator steps when trying to ‘analyse’ what the Macau revenue numbers mean in advance of company reporting.

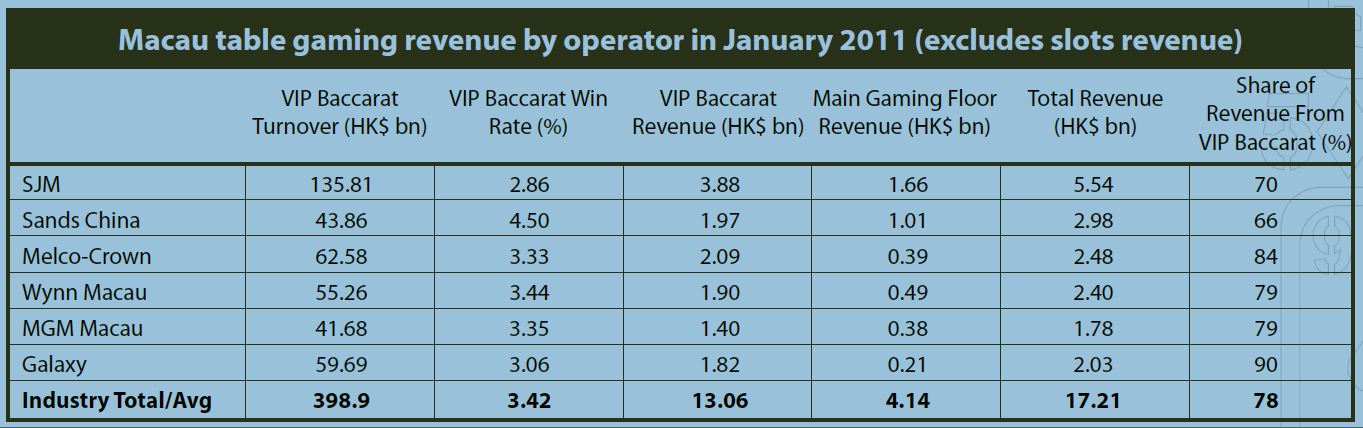

While all businesses in all markets are subject to variables (such as adverse weather or bad debt owed by other parties) that can affect year on year comparisons and ultimately profitability, Macau is arguably even more resistant to high quality analysis and forecasting on an operator by operator basis. This is because gaining a real insight into the dynamics affecting the relationships between junkets and individual operators is difficult. There’s a lot of chatter in the market but little hard evidence ever likely to make its way into a US Securities and Exchange Commission filing. But in a market currently 78% dependent on VIP gaming (the January figure) for its gross casino revenue, one can’t blame a fellow for trying.

|

The problem is certainly not in identifying general market trends. That trend is clearly one of expansion. Casino revenue in Macau surged 33% year on year in January to 18.6 billion patacas (US$2.3 billion) from 13.9 billion patacas, according to data from Macau’s Gaming Inspection and Coordination Bureau. Union Gaming Research estimated additionally in a recent note a 10% year on year increase in visitor numbers during this Chinese New Year, though as Union Gaming points out, that could have been partly attributable to depressed numbers in 2010 when there was unusually cold weather during the equivalent holiday period.

The problem arguably in Macau is both to understand the impact of the direct human relationships involved in the junket casino courtship and also in calibrating market risk as it applies to issuance of VIP credit. The latter is especially important given that nearly 80% of Macau’s gaming revenues currently pass through the hands of third parties; i.e. those junket operators, before reaching the concessionaire’s books.

Clear as mud

|

| Flight risk-relationships between junkets and operators are sometimes made more like love affairs than businss |

Despite some innovations such as the listing of junket entities in Hong Kong that theoretically at least suggest a trend towards transparency, in practice Macau junket o p e r a t i o n s are still very opaque by the standards of modern businesses in most developed economies. That’s in terms of the way they issue credit and the way they collect that revenue after it’s actually been recorded by the casinos (not as a receivable, but as actual revenue). More on that in a moment.

The elephant in the Macau VIP gaming room is that with 60% of Macau players overall coming from the Chinese mainland, and gambling debts being unenforceable via the courts in the People’s Republic, if a player doesn’t honour his credit, someone, somewhere, may have to be leaned on pretty heavily by foot soldiers indirectly kicking back up to the junket operators. That’s about as opaque as it’s possible for a business to get and not be technically labelled as racketeering.

“Chinese gamblers could be the biggest single credit risk currently facing the Las Vegas market”

In defence of the junket system, it’s difficult to see an alternative way of running high roller operations in Macau given non-execution on gambling debts incurred by Chinese citizens and the currency and banking controls currently limiting overt cross-border movement of large amounts of money out of and into China.

Year of the rabid gambler

Indeed, Chinese gamblers could be the biggest single credit risk currently facing the Las Vegas market. Last month, the Las Vegas Sun newspaper reported Vegas casinos are owed at least US$80 million from gamblers in China and Hong Kong alone. That puts into perspective the HK$100 million-plus debt recently reportedly incurred by one gambler in Macau. The internationalisation of the player market in Las Vegas may be welcomed as a much-needed boost during domestic economic slowdown. But at least credit issued to domestic US players can be recovered via the courts.

This is not to say that the in-house credit issuance system used by Las Vegas casinos is entirely without risk or indeed entirely without opacity even when dealing with domestic players rated by a centralised credit bureau. The Las Vegas Sun also reported last month that while a Vegas gambler’s first marker triggers an application process and a bank inquiry akin to taking out a personal loan, subsequent markers involve little paperwork other than acheck of the person’s gambling history with Central Credit, a credit reporting bureau for the casino industry. This can create perverse incentives for a casino host who already has a personal relationship with a player and is paid according to the player’s level of roll. It can encourage a host to in turn encourage his employer to keep the credit lifeline open.

Default can swiftly lead to litigation in the US system, though settlement via the courts may take many years in some cases. One encouragement for Vegas gamblers to pay up is that although a casino debt is a civil matter in common with the rest of the US, in Nevada is it also a felony offence that can lead to arrest and a prison sentence. According to the Las Vegas Sun, the Clark County District Attorneys office processes about 100 marker cases each week and thousands a year involving big Strip resorts and smaller, neighbourhood casinos. That volume has increased by 5% to 10% in the recession, peaking in 2009.

Home visit

In the Macau credit scenario, if person-to-person ‘persuasion’ doesn’t work, and the debt goes seriously bad, the Macauconcessionaires still have to pay the near 40% tax on the creditfuelled gross originally wagered (an early bone of contention with Steve Wynn when he entered the market). In Nevada, operators don’t pay tax on uncollectible player debts. To offset that potential loss of tax revenue to the public purse, the D.A.’s Bad Check Unit is allowed to retain 5% of any monies recovered from successful debt recovery to cover departmental and county costs. That compares favourably with the 20% fee charged by many commercial debt recovery companies. Union Gaming Research says that bad debt expense on the Las Vegas Strip in financial year 2009 (the most recently available data) was about 3.3% of gross gaming revenue (GGR). In 2009, the Strip’s gaming revenues were US$5.5 billion, meaning bad debt amounted to about US$181 million. On those metrics (notwithstanding the fact 2009 was adversely affected on the revenue and debt sides by the economic downturn), Chinese gamblers could be responsible for nearly half of the Las Vegas Strip’s annual gambling-related bad debt.

There is some anecdotal evidence that debt default rates may be historically higher in Macau than on the Las Vegas Strip. Back in 2005, Jorge Oliveira, then commissioner for legal affairs in the Macau Gaming Commission, suggested a Macau system for write offs capped at the equivalent of 6% of annual GGR. That figure may have been an estimated one rather than one scientifically researched, but it’s interesting to note that over the past 20 years, bad debt on the Las Vegas Strip has averaged only 3.1% of GGR annually, according to figures collated by Union Gaming Research.

While recent reports of a small outbreak of VIP bad debt may be limited to a tiny number of players and may be only a fraction of 1% of total Macau VIP revenue, it does illustrate one potential market risk involved in reliance on the high rollers. That reliance may eventually change largely as a function of the expected growth of the Chinese middle class. Those ‘non-comped’ middleincome mass-market players may be more inclined to divert some of their cash to goods and services such as shopping, restaurants and hotels, so that Macau becomes the multi-night tourism destination it aspires to be.

And that brings us to the January revenue numbers. The sell offs seen in Las Vegas Sands Corp’s stock on 7th February after reopening of Asian markets post-Lunar New Year holiday may be as much a function of profit taking (in a region with a lot of retaillevel investors that see the New Year as an auspicious moment in the business cycle) as it was global market disappointment in LVS’s fourth quarter 2010 revenue (as suggested in sections of the financial press). Looking at LVS’s Macau metrics for January, the company has the highest exposure of all the concessionaires to the mass market (where market-wide, gross margins can be 35%) and the least reliance on the VIP segment (where volumes are huge but market-wide margins are typically 7% to as little as 3%). That above market average contribution from the mass segment can only be good news in terms of return on invested capital in the medium to long term.

Sands China’s better balance between VIP and mass also arguably offers a more stable business model than some of its rivals, providing some cushioning against potential macro shocks. Taking up the ‘lies, damned lies and statistics’ theme again, gaming revenue figures alone don’t give weighting to the potential hedging factor provided by the multiple revenue streams offered by an integrated gaming resort such as The Venetian Macao.

Steady as she goes

The risk implied in Galaxy Entertainment Group’s current 90% weighting toward VIP baccarat is probably offset to some extent because of its reputation around town for good relationship management with junkets. Some operators blow hot and cold with junkets, suddenly hiking up their offer on revenue share or profit share when pressure to grab more VIP market share builds up from investors (a typical short cycle Western investment model). Galaxy seems to prefer a slow and steady approach. The fact the Lui family and ‘connected persons’ still hold a majority stake in GEG is probably a factor in creating that consistency. Galaxy’s overall dependence on high roller play is also likely to reduce significantly when the predominantly mass-market Galaxy Macau resort opens on Cotai later this year.

|

| Sands China’s better balance between VIP and mass also arguably offers a more stable business model than some of its rivals, providing some cushioning against potential macro shocks |

Melco Crown Entertainment, weighted in January at 84% dependence on VIP play, has form when it comes to heavy discounting on its end as a way of attracting high roller volume, as witnessed by the commission wars sparked by the VIP-focused Crown Macau (now Altira) four years ago. But MPEL does at least have two clubs in its golf bag. City of Dreams on Cotai is designed (in theory) for mass market entertainment. As such has the space (if not the clarity of layout) to expand its mass market offer as circumstances and the Macau government allow.

At MGM Macau, Wynn Macau and Encore at Wynn Macau on the peninsula, VIP business accounts for an above market average 79% of gross revenue. The two operators have already seen some month to month volatility in market share ranking—a function, according to some sources, of the two properties tussling for access to the same VIP business. Both operators plan Cotai projects. Wynn’s appears further down the track in terms of the planning, though the idea of a 2013 opening seems to have been knocked back by the government’s apparent moratorium on immediate further expansion of gaming capacity on Cotai. According to Steve Wynn’s assessment in June last year, Wynn Cotai would be more a case of Wynn Macau super-sized than ‘Venetian 2.0’. But things can and do change in response to market conditions. Back in 2006, Mr Wynn referred to the possible creation of some mid-market accommodation at Wynn Cotai as “a Taiwan guest house”.

Macau is a market that is not only in thrall to the junket operators. It is also a market where the junket sector itself has seen consolidation, with smaller operations coming under the branding of larger entities acting as junket investors. Those investors have in turn provided the working capital that has helped to expand high roller play so effectively. That means that in many cases a junket investor/operator/consolidator is working with several casino operators simultaneously. That enables the junkets not only to compare the deals on offer from operators for their VIP business, but also makes the casinos’ management of the operator-junket relationship a key component in creating VIP volume and ensuring business retention. Whether that relationship is driven principally by price or by more intangible factors such as goodwill is potentially a multi-billion dollar question.