Macau’s casino boom is outstripping its labor supply. Looking ahead to the next wave of megaresort openings, many are calling on government to relax its ban on non-resident dealers. But that’s a big nonstarter, socially and politically. More creative solutions will be needed. And some of them are already taking shape

Ah Mei got a relatively late start working as a dealer in Macau. She took up the job three years ago at the age of 43 for a simple reason—money.

“What other job in Macau can offer somebody like me MOP17,000 [US$2,125] a month?” says the Guangdong native, who never finished high school and now works at Pharaoh’s Palace, a satellite casino operating under the license of SJM Holdings.

Arriving in Macau from the mainland in the late 1980s, she had held a variety of menial jobs, cleaning, waitressing and working at a garment factory, to supplement her four-member family’s income.

“My husband didn’t like the idea [of me working as a dealer] at the beginning, worrying I would develop a gambling habit,” she says. “But we needed money at the time because my elder son was about to start university.”

It’s becoming increasingly common for Macau’s six casino operators to target middle-aged locals like Ah Mei as the city’s labor crunch worsens. The unemployment rate stood at 1.7% in the three months to May, well below the rate considered to represent full employment, and many of the remaining 6,400 workers seeking positions are either merely between jobs or are so lacking in skills as to be virtually unemployable. That, coupled with the ban on nonlocals working as dealers, has raised concerns of a severe labor shortage ahead of the second wave of resort openings on the Cotai Strip starting next year, with at least six new properties or major expansions scheduled to open between 2015 and 2017.

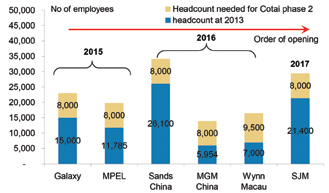

Macau’s six gaming operators are by far the city’s biggest employers, with 83,300 resident and non-resident staff—or nearly a quarter of the employed population—including 25,250 dealers, government figures for the end of 2013 show. The vacancy rate in gaming companies stood at 3.4% over the same period compared with 10.2%, 6.2% and 11.7% in the other major segments of retail, hotels and restaurants, respectively.

Although the deep-pocketed casino operators have been better able to fill vacancies than employers in other sectors, even they could struggle to meet their manpower needs as Cotai’s expansion ramps up.

“In order for Macau to keep growing and provide a better life for people who live here, then this expansion of opportunity has to be coupled with enough people to deal with the visitors that come here,” said Steve Wynn, chairman of Wynn Resorts and its local subsidiary Wynn Macau, during a media briefing in May. His US$4 billion Cotai project, Wynn Palace, will require roughly 9,000 workers when it becomes operational in 2016.

Mr Wynn did not go as far as calling on the Macau government to change its labor policies. A foreign operator would undoubtedly feel uneasy making such a politically sensitive demand. Rival SJM, founded by local casino mogul Stanley Ho, has no such qualms, however. “We, the industry, certainly think it best if croupier positions are open to migrant workers,” Chief Executive Ambrose So said earlier this year. SJM’s upcoming Cotai property, the $3.9 billion Lisboa Palace, will need 8,000 workers when it opens in 2017.

Analysts Praveen Choudhary, Alex Poon and Thomas Allen of investment bank Morgan Stanley say the sector will need 117,000 workers following the resort openings between 2015 and 2017, an increase of 38%, or 32,000, above the current level. More than half of these, some 18,516 workers, will need to be locals, including 12,600 dealers, based on a combined 1,800 table games at the six new projects, with each table having to be manned by seven dealers.

“We estimate a supply of only 700 local higher-education graduates per annum joining the gaming industry and potentially approximately 1,900 local staff that might be available to transfer internally. This implies a shortfall of approximately 13,800 local employees,” they stated in a recent client note.

“Each [Cotai] Phase 2 project could start with only 100-150 tables in both the first and the second year versus our base [estimate] of 300 tables, implying a 10% to 16% reduction in Phase 2 valuation.

” Even that base estimate of 300 tables is far short of the 500- 700 tables requested at each project by the operators, though the government’s 3% cap on the annual growth of tables through 2022 precludes the granting of those requests in full.

Morgan Stanley’s view is echoed by David Bain of brokerage Sterne Agee, who in a note in late June highlighted the tight labor market as a continual concern for the sector.

The government has so far insisted that natural growth of the labor force amounting to 20,000 new local and non-local employees a year will meet the needs of the new Cotai developments. The government’s Policy Research Office estimates the city will require 40,000-45,000 new workers across all sectors by 2016.

Through the first quarter of this year, Macau’s total labor force has increased 16.8% in the past three years to 384,200. Of the new workers, 17,100 were locals, a number just shy of the Morgan Stanley estimate of 18,516 new local employees required to staff the second wave of Cotai over the next three years.

Davis Fong Ka Chio, director of the Institute for the Study of Commercial Gaming at the University of Macau, agrees with the government view that the labor issue is “not as serious as one imagines”.

A member of a government-led committee advising on the city’s economic and human resources policies, he says, “My estimate is that the new resorts opening in Cotai will need 60,000 workers in total in the next few years, an amount that the natural growth of our labor force can supply including immigrants and thousands of new graduates from the universities each year.”

The Morgan Stanley forecast does not account for thousands of foreigners who become Macau “locals” each year by obtaining residency. According to the Macau Identification Services Bureau, 21,316 people became non-permanent residents over the past three years, most of them from mainland China. Among the 13,620 mainland immigrants in the 2011-2013 period, more than two-thirds were between 21 and 50 years old.

Labor leaders such as Ieong Man Teng, president of a group called Forefront of Macau Gaming, acknowledge the supply of local workers “may not be enough” if the new projects get all the tables they have applied for. But their response has been to pressure the government by mobilizing street protests—two in the last year involving thousands of participants—against the “relentless expansion” of gaming and the possibility of dealer positions being opened to non-residents.

Says Mr Ieong, “The only solution to this problem is for the government to strictly fulfill its pledge of capping the growth of the number of tables.”

It’s a position that counts heavily with a political leadership that desires above all to avoid any overt displays of popular discontent.

As Mr Bain has noted, “While certain options have been presented internally within the Macau Government to relax certain labor restrictions—namely to allow for non-Macau residents to hold certain positions that can only currently be assumed by Macau residents, such as dealers—pushback from locals has prevented any true political progress to date.”

SCREWING DOWN THE CAP

In the wake of last year’s protests, Macau Chief Executive Fernando Chui Sai On pledged dealer positions would remain off-limit to nonresidents “as long as I am still in office”. Mr Chui’s first five-year term will end in December, but he is almost certain to be handed a second term by a pro-Beijing electoral committee that is controlled by the city’s leading business and commercial interests.

“[The ban on non-resident dealers] is not about protecting certain types of people but rather about safeguarding social stability,” says Kwan Tsui Hang, vice president of the city’s largest labor group, the Macau Federation of Trade Unions, and a member of the Legislative Assembly. “It is about providing opportunities to Macau residents— particularly the middle-aged and the low-skilled—to obtain a more stable and higher-paying job.”

To accomplish this it is all but certain the government will have to stick closely to its own yearly cap on new table games.

“We do not rule out that the [new Cotai] projects can get all the tables they have requested—namely 500-700 tables each—10 years later,” Secretary for Economy and Finance Francis Tam has said. “But for the 10 years starting 2013 we are certain that the government will not grant all the tables each project has requested … based on the annual rate of increase of no more than 3%.”

Between 2006 and 2009, 75,691 new local and non-local employees—an average of 18,923 a year—were sufficient to support at least 15 new casino hotels that opened during the period, including The Venetian Macao, City of Dreams, Wynn Macau, MGM Macau and Grand Lisboa. The number of dealers shot up by 14,688 over the same period to serve the additional 3,382 gaming tables, with 4.3 dealers manning each table, versus Morgan Stanley’s assumption of seven dealers per table.

Should the cap be strictly adhered to there will only be 1,646 incremental new tables allocated to the new projects, Credit Suisse analysts Kenneth Fong and Isis Wong estimated in their latest report on Macau gaming.

“If the government approves all the table requests and projects open at the same time, this would create a huge pressure on wage costs and local SMEs, and potentially cause social discontent. This is what the Macau government doesn’t want to see,” they said.

David Chow, co-chairman and chief executive of resort operator Macau Legend Development and a former legislator, believes the government has the situation under control.

“The pace of gaming development can be controlled by the government, not by the gaming companies,” he says. “If all the projects open at the same time, I really don’t know how they can operate. But if the openings can be staggered into different phases I don’t think it will be that difficult.”

Macau Legend owns the Pharaoh’s Palace, which is located in the company’s Landmark Macau Hotel, and a second SJM satellite casino, the Babylon, located at the company’s Macau Fisherman’s Wharf outdoor leisure complex near the city’s main ferry terminal. Fisherman’s Wharf is in the midst of an expansion and makeover slated for completion in 2017. Mr Chow is hoping to get an additional 350 gaming tables at the complex, and he will need 5,000 more workers.

HELP FOR THE AGING

In view of the government’s current reluctance to make any changes to its labor policy, casinos are seeking other solutions. Technology could be a big part of the answer.

At the Macau Jockey Club Casino, which reopened on 30th April after a decade of closure, chipless e-baccarat tables supplied by gaming equipment manufacturer Paradise Entertainment have paved the way for the hiring of older, lower-skilled dealers who previously were not considered suitable by casinos.

“The digital interface speeds up the game, with automatic payouts doing away with the need for dealers to do mental calculations. Calculating the 5% commission on banker wins was quite difficult for some of them,” says Jay Chun, chairman and managing director of Paradise Entertainment. “[The e-baccarat table] provides a new solution to the dealer shortage Macau will face in the coming years.”

Mr Chun calculates that by using e-baccarat tables and the chipless system, the Macau Jockey Club Casino has reduced its staffing requirement by two-thirds.

Morgan Stanley says deploying more electronic gaming tables and improving productivity could help ease the city’s labor shortage, but warns: “ETGs are generally less appealing to gamblers, resulting in lower yield per total machines combined than an equivalent table.”

For the University of Macau’s Davis Fong, part of the solution hinges on adapting to certain demographic realities. “The question right now is whether casinos will be willing to put forward less youthful faces to their customers on their front lines,” he says, adding that “more than a few” middle-aged residents would be willing to work as dealers if casinos welcomed them.

“As the majority of casino customers are from mainland China, I don’t believe it will be a problem for casinos to use middle-aged dealers because many of them speak the same language as the customers—Mandarin.”

The Macau Gaming Industry Workers Association, an affiliate of the Federation of Trade Unions, has been offering vocational training courses for prospective dealers since 2003, teaching basic baccarat knowledge and language skills. “Many of those enrolling in our courses now are female, middle-aged, not well-educated, with low monthly income, and some are recent immigrants,” says the association’s vice president, Leong Sun Iok. “They want to work as dealers to improve their livelihood.” And the courses “are always full,” he says. “Over 80% of our students successfully secure dealer jobs. Demand for them is high, especially in light of the current tight labor market.”

About one-fifth of employees in the gaming sector, some 21.2%, were aged between 45 and 54 as of last year, up from 18% in 2004. Across all sectors of the economy, workers between 45 and 54 accounted for 23.3% of the total, down from 25.6% in 2004.

US-based brokerage Telsey Advisory Group believes Macau’s cash rich gaming operators are capable of recruiting all the workers they need. “Today, while labor is expensive, there does not appear to be any lack of supply,” writes analyst Christopher Jones. “Looking further out, casino-based labor is not really a casino problem as operators have the margin and capacity to pay up for the local labor required.”

Wynn Macau announced in March that it will issue 1,000 shares of its Hong Kong-listed stock to each of its 7,500 employees. In July, Melco Crown Entertainment unveiled a bonus scheme for its staff that includes a one-off handout equivalent to six months’ salary. Sands China revealed in the same week that it will add a second month’s pay to its annual bonus package.

The average salary in the gaming sector stood at MOP19,120 (US$2,390) at the end of 2013. Mr Leong of the Macau Gaming Industry Workers Association believes it will soon rise above MOP20,000, with operators offering even more incentives to attract and retain workers.

But this will not come without an impact on the bottom line. Mr Jones cautions that an expected 5-10% annual increase in labor costs could create “risk” for profits, pointing out that “labor is the third-greatest expense for operators after gaming taxes and junket commissions.” He says, “Macau will need a more progressive labor policy which allows for increases in foreign labor, though this seems almost entirely unlikely until the next chief executive election.”

“Whether the Macau government will introduce any changes to its labor policies is still debatable, but it will not venture anything this year, which sees the election of the chief executive and the 15th anniversary of Macau’s return to China, as Beijing emphasizes prosperity and stability,” says Zeng Zhonglu, a professor at the Gaming Teaching and Research Centre of Macao Polytechnic Institute.

Political activism has flared up in recent months—some refer to it as Macau’s political awakening—after the city witnessed on 25th May the largest protest since the 1999 handover, with residents taking to the streets to voice their opposition to a lavish perks bill for outgoing government officials.

Meanwhile, although working as a dealer is helping Ah Mei put her son through university, she clearly does not want him to follow in her footsteps after he graduates.

“There is no way I’ll let him become a dealer, otherwise why would I be paying for him to go to university?” she says. “I would prefer he work in a bank or for the government.”